“I wanted not the momentary suspense but that whole world to which it belonged.”1

In one of his essays, C.S. Lewis elaborated on an idea that has since taken on a life of its own. The idea—that story is the most effective carrier of truths that might be rejected by an audience receiving them in a more direct form—wasn’t new when he wrote about it. The “moral of the story” has a long and storied history. Søren Kierkegaard promoted the imparting of truth via indirect means. Emily Dickinson told the truth but told it slant. And Jesus’ parables elucidated the founding principles of the kingdom of heaven.

Lewis’ catchy terminology—sneaking past watchful dragons—pops up among fantasy literature aficionados and Christian writers, readers, and other parties interested in how stories might impart to an audience profound truths about God, the world, and the rules and rewards of a good life. In a 1956 New York Times piece (published a couple months after the last of the Narniad hit bookshops), Lewis discussed how the Christian gospel found its way into his fairy stories. (And, perhaps, how Christianity might have been better rooted in him as a child in such a way that it would have precluded his atheist turn as a young man.)

I thought I saw how stories of this kind could steal past a certain inhibition which had paralysed much of my own religion in childhood. Why did one find it so hard to feel as one was told one ought to feel about God or about the sufferings of Christ? I thought the chief reason was that one was told one ought to. An obligation to feel can freeze feelings. And reverence itself did harm…

But supposing that by casting all these things into an imaginary world, stripping them of their stained-glass and Sunday school associations, one could make them for the first time appear in their real potency? Could one not thus steal past those watchful dragons? I thought one could.2

He goes on to say:

The inhibitions which I hoped my stories would overcome in a child’s mind may exist in a grown-up’s mind too, and may perhaps be overcome by the same means.

These means—casting real things behind the veil of fantasy—were not the only way Lewis communicated what he believed to be true, but it seems to be the way he came to prefer. He wrote two years before his NYT piece:

…we needn’t all write patently moral or theological work. Indeed, work whose Christianity is latent may do quite as much good and may reach some whom the more obvious religious work would scare away. The first business of a story is to be a good story.3

And, in 1955, in response to a request to write for Christianity Today, Lewis said:

I do not think I am at all likely to write more directly theological pieces. The last work of that sort which I attempted had to be abandoned. If I am now good for anything it is for catching the reader unawares—thro’ fiction and symbol. I have done what I could in the way of frontal attacks, but I now feel quite sure those days are over.4

Many (myself included) have taken Lewis’ cue, presuming that the best way to impart spiritual, moral, universal ideas to an audience is through stories, especially those where truths are deliberately disguised. Lewis did this in all his fiction, most popularly in The Chronicles of Narnia. Dr. Simon Horobin,5 a professor of English Language and Literature at Oxford, sums up the common view:

The Narnia stories offer powerful, striking ways of presenting Christian truths in ways that effectively sneak past the watchful dragons of secularism and our own sinful nature and give us access to real treasure, treasures in heaven where thieves cannot break in and steal.6

Effectively sneak past. Sometimes, sure. But not always.

Miller time

“…for all the countless times I have reread Lewis’s books, they have never succeeded in converting me.”7

I’ll stake a lot on the ability of a story to sneak past a soul’s watchful dragons. You’ll find no bigger enthusiast of the power of symbology and subtlety in story—concepts expounded on by writers and thinkers such as the aforementioned Kierkegaard, Malcolm Guite, and Andrew Peterson. But what happens when the dragons awake? What happens when the reader sees through the veil—and feels betrayed?

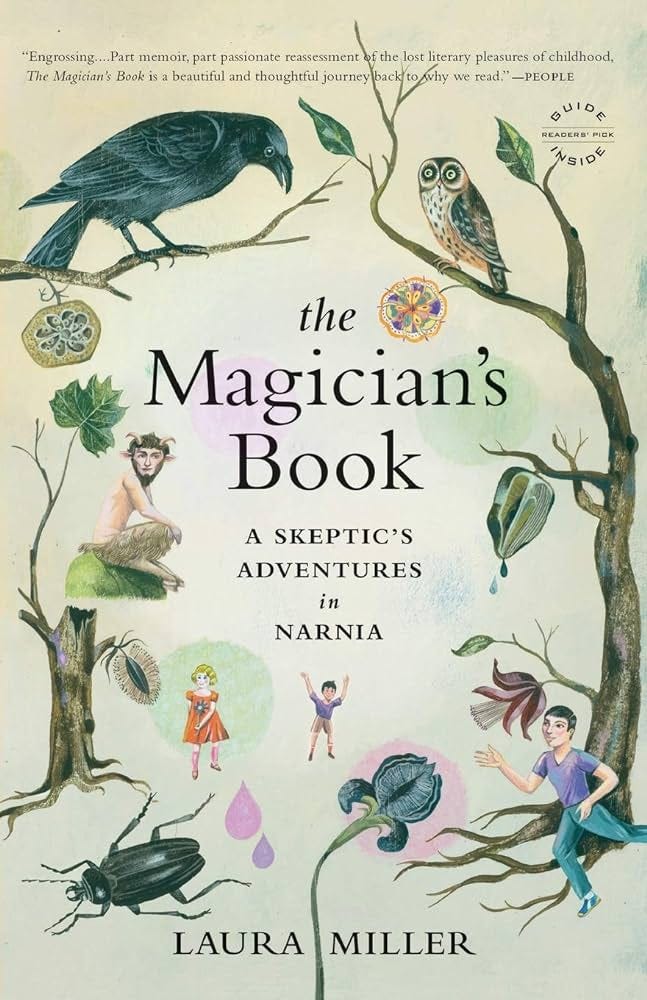

Laura Miller, journalist, literary critic, and co-founder of Salon.com, loved reading and loved Narnia as a child. “It was [The Lion, the Witch, and the Wardrobe] that made a reader out of me,” she says in her literary memoir The Magician’s Book: A Skeptic’s Adventures in Narnia. “It showed me how I could tumble through a hole in the world I knew and into another, better one, a world fresher, more brightly colored, more exhilarating, more fully felt than my own.”

Despite being raised Catholic, she only realized Narnia’s Christian underpinnings while reading Lin Carter’s study of modern fantasy, Imaginary Worlds, much later. She learned Lewis

was famously Christian, a fact I’d somehow managed to miss. I was shocked, almost nauseated. I’d been tricked, cheated, betrayed. I went over the rest of the Chronicles, and in almost every one found some element that lined up with this unwelcome and, to me, ulterior meaning.

She goes on…

I was horrified to discover that the Chronicles of Narnia, the joy of my childhood and the cornerstone of my imaginative life, were really just the doctrines of the Church in disguise. I looked back at my favorite book and found it appallingly transfigured… I felt angry and humiliated because I had been fooled.

Well, that’s certainly not the result Lewis was going for. But Miller who, like Lewis, felt her religion paralyzed in youth, is not alone.

Filmmaker Guillermo del Toro reportedly turned down the opportunity to direct a Narnia film because “as a lapsed Catholic, he couldn’t see himself bringing Aslan the lion back to life.”8 He said in 2006, “I really enjoyed [Lewis] as a kid, but he’s too Catholic for me. It’s not something as an adult I can feel comfortable relating to.”9

Neil Gaiman, fantasy writer extraordinaire who credits Lewis as the author who made him want to write, holds similar feelings to Miller and del Toro. In a 2004 speech to the Mythopoeic Society, he said:

For good or ill the religious allegory, such as it was, went entirely over my head, and it was not until I was about twelve that I found myself realising that there were Certain Parallels. Most people get it at the Stone Table; I got it when it suddenly occurred to me that the story of the events that occurred to Saint Paul on the road to Damascus was the dragoning of Eustace Scrubb all over again.

I was personally offended: I felt that an author, whom I had trusted, had had a hidden agenda. I had nothing against religion, or religion in fiction—I had bought (in the school bookshop) and loved The Screwtape Letters, and was already dedicated to G.K. Chesterton. My upset was, I think, that it made less of Narnia for me, it made it less interesting a thing, less interesting a place.10

I don’t know how many people Miller interviewed about Narnia for her book, but she found a handful whose experiences mirror her own. A few felt truly betrayed, their dragons enraged, but others felt meh about the real-world Christianity seemingly at the center of the Narniad.

losing Narnia, choosing truth

“…death wasn’t especially interesting to me, and animals were.”11

I discovered The Magician’s Book while researching for my own Narnia memoir. (Miller and I have entirely different thoughts on Prince Corin.) I read it because I’m interested in what happens when the watchful dragon wakes. My introduction to Narnia came within a thick Christian context: the Passion parallels in The Lion, the Witch, and the Wardrobe I likely took for granted when I first read them. After all, dying and resurrecting gods are everywhere if one has eyes to see.

Overall, The Magician’s Book is a good read: insightful, interesting, intriguing. She aptly describes her “relationship to Narnia”: “as rocky as any love affair, a story of enchantment, betrayal, estrangement, and reunion.” I’d recommend it (the book, not the rocky love affair) to anyone interested in the effects of literature during childhood: there are excellent insights on the reading experience and how children view the world. Honestly, I loved it, except for the parts where Miller casts Lewis as a trickster.

She mischaracterizes Lewis’s story-making as a scheme he set starting out:

…his plan was to strip the theme of Christianity’s unattractive “externals,” its “stained-glass and Sunday School associations,” in hope that his young readers would then perceive these themes “in their real potency.”

Lewis didn’t intend his audience to recognize what he was doing, or at least not right away. [It was his] attempt to elude the defenses readers set up against authors and stories that aim to teach them something for their own good.

Obviously, that view skews the origin of the Narnia stories. Narnia began with a series of convoluted images—“a Faun carrying an umbrella and parcels in a snowy wood”—that demanded a narrative. Lewis’ “first business” was to make a “good story”—the Christian elements are incidental.

Miller goes on to raise more interesting questions, however:

…it’s worth asking whether the stained-glass and Sunday school associations aren’t as much a part of Christianity as the mystical Resurrection of Christ, even if they aren’t supposed to be as important a part. Is a religion a great story about the meaning of life or a daily practice, or is it perhaps something else—a collection of icons?

She quotes Karen Armstrong’s Battle for God to bolster the idea that Lewis’ attempt to divorce Christianity from its “unattractive externals” was flawed from the start. Armstrong writes:

Myth only became a reality when it was embodied in cult, rituals, and ceremonies, which worked aesthetically upon worshipers, evoking within them a sense of sacred significance and enabling them to apprehend the deeper currents of existence.

Miller misses the deeper magic that myth also becomes reality through story, through history. It’s not bells and incense that give Christianity its potency. The bells and incense, the Eucharist and other Sacraments are feeble attempts to commemorate and depict the indemonstrable potency of mythic-historical truth.

By the time Lewis got around to writing Narnia, he’d become a profound explicator of such mythic-historical truth many times over. He’d written Pilgrim’s Regress, The Problem of Pain, The Screwtape Letters, Mere Christianity, and Miracles before The Lion, the Witch, and the Wardrobe. It’s not like Lewis couldn’t get at these ideas without the trappings of story. He spoke of Reality with those other writings; with Narnia, he spoke of Myth.

Miller tries to have her cake and eat it too, making the bold claim that Narnia needn’t be a really Christian story at all:

So when Lewis’s child readers don’t see Christianity in the Chronicles, they are in fact perceiving a truth about Narnia that adults usually miss. The Christianity in Narnia has been substantially, rather than just superficially, transformed—to the point of being much less Christian, perhaps, than Lewis intended.

Madam, which is it? Are all the cultural and symbological adornments of Christianity part and parcel of the religion, or not? Does Lucy find Aslan by another name in our world, or does she not?

I suspect Miller still desires not just the momentary Narnian suspense but the whole world to which it belongs. She admits as much.

But all of this is an aside. I am not so concerned about Miller’s particular experience with the Narniad as I am with our preoccupation—the preoccupation of Christian storytellers—that the best stories are ones subtly imbued with truths that slip past the readers’ conscious guardians of self-interest and worldliness to deposit seeds that, one day, might flourish into the knowledge of the divine. If The Chronicles of Narnia is the best way to do that, I am concerned about what happens when it doesn’t work…and why.

fundamentally disinclined?

Miller, Gaiman, and others share an experience that I don’t: falling in love with Narnia as children before realizing that Aslan can be read as Jesus and the Stone Table as the Cross, etc. Miller offers two reasons why some don’t pick up on these themes upon first reading Narnia. The first is that young children don’t know enough about the world yet to draw such comparisons. She writes:

To someone who has heard and read many stories about the self-sacrifice of god-kings or other saintly heroes who suffer for the salvation of others, Aslan is obviously an analog of Christ. But to someone who is still encountering instances of the great themes of Western culture for the first time, Aslan cannot be Jesus because Jesus is a bearded man in sandals and robe, while Aslan is a lion.

Fair enough. Her second reason is that people are simply differently dispositioned. Miller suffered from the same impression of Christianity from childhood as Lewis did. She testifies that her mildly Catholic upbringing persuaded her that “unhappiness was next to godliness and that virtue was consolidated by suffering.” Christianity, to her, contained a “drab, grinding, joyless view of life.” And Narnia was her “sanctum.”

…Narnia was so incompatible with my understanding of Christianity that it never would have occurred to me to connect the two.

…Narnia was liberation and delight. Christianity was boredom, subjugation, and reproach... The Christianity that I knew—the only Christianity I was aware of—was the opposite of Narnia in both aesthetics and spirit... For me, Narnia was Christianity’s antidote.

Miller didn’t just get teed off upon finding out about Narnia’s Christian underpinnings; she saw the Narniad as the antithesis of the Christianity she knew. Still, she considers that the real fault might lie with herself rather than the stories.

Skepticism, like faith, is more a matter of temperament than indoctrination. Any one of a half-dozen serious flaws in any theological worldview can undermine the beliefs of someone who doesn’t much want to believe in the first place.

She contrasts her experience with that of Tiffany (a reader she interviewed) who “is a believer by constitution, even if what she believes in has changed over the years.” Tiffany was ‘jarred’ when the parallels between Narnia and the Christian story became obvious. She eventually left the denomination of her childhood but keeps returning to the church despite its flaws. The books, to her, are a “kind, sweet metaphor for Christianity” as it should be.

Perhaps we’re troubled by these different reactions because we’re thinking about the question from the wrong end. The question is not whether Lewis crafted his story well enough to both conceal and reveal the euangelion it contained. The actual (and more uncomfortable) question is (as Miller puts it): “Can a book win over a soul who is fundamentally disinclined to believe?”

For what it’s worth, we might need to be more concerned with the audience and less with the stories themselves. Even Lewis seems to admit as much in his ‘Fairy Stories’ essay, suggesting the prescribed method of giving watchful dragons the slip might only work for some.

The Fantastic or Mythical is a Mode available at all ages for some readers; for others, at none. At all ages, if it is well used by the author and meets the right reader, it has the same power: to generalise while remaining concrete, to present in palpable form not concepts or even experiences but whole classes of experience, and to throw off irrelevancies. But at its best it can do more; it can give us experiences we have never had and thus, instead of ‘commenting on life’, can add to it. I am speaking, of course, about the thing itself, not my own attempts at it.

I’m thinking Miller and Lewis agree: different sorts of stories appeal to different sorts of people and no one believes unless they want to.

Maybe we should have less faith in our stories because, ultimately, it’s desire (or, in Laura Miller’s suggestively Calvinist term, disposition) that leads to belief. Both a mythical story perfectly in the mode that C.S. Lewis avers is best, and a story that isn’t in that mode at all, might slip past a sleeping dragon or wake it to flame and fury. The reason lies with the audience as much as with the author.

In the end, some arrive further up and further in, and others further down and further out. It all depends on where we want to be.

Remember your fairy tales. Spells are used for breaking enchantments as well as inducing them. And you and I have need of the strongest spell that can be found to wake us from the evil enchantment which has been laid upon us.12

asides + signal boosts

At the risk of torpedoing this entire piece, I’m linking to a little post on a book review blog that I ran across while writing this post. The writer mirrors my unvarnished and pragmatic thoughts on the whole idea of a reader feeling betrayed by a story. In part:

I’ve heard of so many people who say [they] feel cheated when they discover that there are parallels between these [Narnia] stories and Christianity, and I find the whole thing bizarre. Authors write about issues that interest them, and C.S. Lewis was interested in Christianity, so—hey, big surprise!—Christian themes inform his books. I can see not liking that, because maybe you aren’t interested in Christianity, at least Lewis’s version of it, but this betrayed feeling is weird to me. The books have themes that inform the entire story, just like every good book ever.

…The Narnia books aren’t sneakily advancing a Christian agenda for propaganda purposes. They’re written by a Christian person. [Duh!]

Yeah, this substack could’ve been a tweet, but that wouldn’t have been as fun. You can read that whole post here.

Spoiler alert! I finally caught up on Loki Season 2. It took me a couple episodes to get into it, but in the end, Loki did what gods do—laid aside his self-interest to protect his friends, gathered up the threads of time, took the burden of the multiverse on his shoulders (quite literally), and ascended to the throne of He Who Remains. He realizes that “purpose is more burden than glory.” (I wonder just how long the writers have been sitting on that line because—if you remember Loki’s introduction to the MCU—the turn is glorious.)

Now that I think about it, Loki’s sacrifice, his laying down his life to protect his friends, his solitary ascent through darkness to uphold all of time, reminds me of another story about the son of a god in our world—hmmm.

Actually, never mind. Just know Loki Season 2 is worth watching for the finale alone.

My friend Katy is now hosting her blog, Finding Chaya, on Substack. Check it out.

C.S. Lewis, Of Other Worlds: Essays and Stories

C.S. Lewis, “Sometimes Fairy Stories May Say Best What’s to be Said,” https://apilgriminnarnia.com/2019/05/30/fairy-best/

From a letter to Cynthia Donnelly in 1954.

Quoted in Hide and Seek: The Sacred Art of Indirect Communication, by Benson P. Fraser

During Dr. Horobin’s thoroughly interesting Hutchmoot UK 2023 presentation, “Narnia: The Monsters and the Skeptics,” I asked about the matters addressed in this post. I’d been thinking about them for some time. He said it deserved more thought but didn’t have an answer at the time. I kept thinking about it, and now there’s this post.

Sue Careless, “Stealing Past the Watchful Dragons,” The Anglican Planet, https://anglicanplanet.net/stealing-past-the-watchful-dragons-2/

Laura Miller, The Magician’s Book: A Skeptic’s Adventures in Narnia

I, for one, would love to see a del Toro interpretation of The Silver Chair.

“Conversations: Guillermo del Toro,” Salon, https://web.archive.org/web/20221219122924/https://www.salon.com/2006/10/13/conversations_toro/

Neil Gaiman, Mythcon 35 Guest of Honour Speech, https://journal.neilgaiman.com/2012/01/speech-i-once-gave-on-lewis-tolkien-and.html

Laura Miller, The Magician’s Book: A Skeptic’s Adventures in Narnia

C.S. Lewis, Weight of Glory

I enjoyed reading this! (hi, I'm a longtime lurker. Elizabeth Sanders sent me here.) I think it would be fun to go into a deeper dive on that conclusion of people going further up and further in because they want to, or don't because they don't want to -- especially in the context of myth, which can have a transformational power even over our own desires. But Narnia isn't a one-size-fits-all transformational myth either, like you said.

I came to this through a spontaneous browse on Reddit's, brought forth by a sudden childish need for having a Christmas of Old (which was always the BBC version of LWW; as Katy mentions production values might be less than the Walden Media movies, but if you can see past that, the series was much closer to the books in spirit) and I just wanted to say thank you for writing this.

My English isn't good enough to debate (agree?) with you in depth (frankly it's been so many years since university that I can probably not even do it in my own language), but I am now going to subscribe to your substack - and go chase up my copy of Till We Have Faces (having devoured all of the Narnia over NY).