this is your brain on pop culture

In love with popular entertainment? Great! It's changing the way your mind works.

I love pop culture. I admit it, even though it feels bad to say.

Being raised alongside so many Fundamentalists vs. The Culture battles leaves one with the Pavlovian impulse to treat whatever is “popular” with suspicion or to straight-up condemn it as being of the devil and a tool of the political elite one disagrees with. (And these two, the devil and your political nemeses, might be the same, so it gets confusing.)

I’ve recovered from that—I think. I’m constantly interested in what’s popular in our broad, collective, shared culture. I’m curious about everything being made and what big audiences are paying attention to—movies, music, television, books, memes, TikTok reels. My dream job1 is knowing what’s in the zeitgeist and why it’s there—even the stuff that’s lowbrow and unclassy.

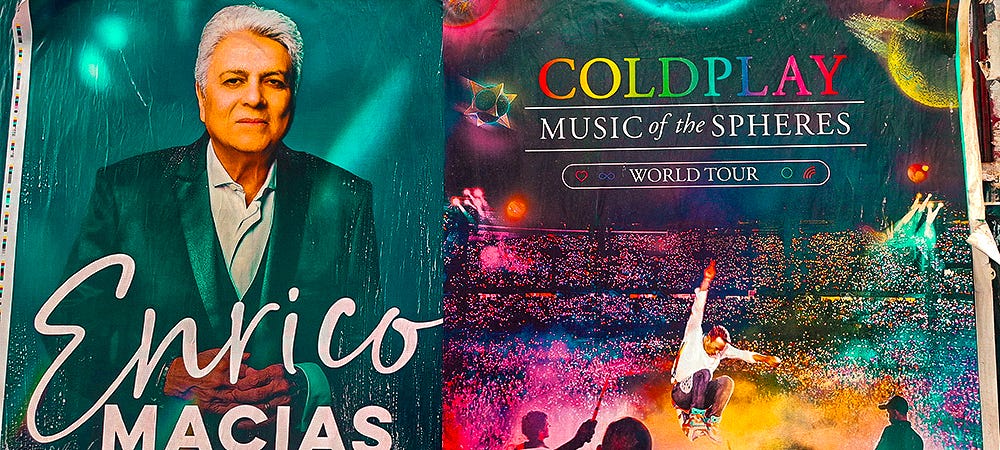

Some of the popular2 things I’ve enjoyed might be classified as “guilty pleasures”—from Taylor Swift to Shadowhunters and YouTube cover bands to the MCU. I’ve been dragged into Attack on Titan and enjoyed a swathe of young adult novels with unnecessarily tortured and over-dramatic love triangles. I’ve enjoyed it all—and not just in a clinical I-want-to-see-what-the-appeal-is way. I genuinely love(d) this stuff.

Some of these enthusiams I’ve grown out of. Some remain. As I’ve ceased thinking about them as ‘guilty pleasures,’ I’ve begun thinking more about how popular culture shapes my psychospiritual framework and our collective cultural framework, and how our participation in popular culture can transform us for good or ill.

first, defining pop culture

Most of us have an idea of what constitutes popular culture. But here’s how the Cambridge Dictionary defines it:

music, TV, cinema, books, etc. that are popular and enjoyed by ordinary people, rather than experts or very educated peopleGot it. “Experts” and “very educated people” do not like pop culture. (😤 I so wanna go there now, but that’s a conversation for another day, and my take on the whole thing would begin somewhere in the area of this other post from early this year.)

I like this definition by Oxford Bibliographies a lot better:

Popular culture is the set of practices, beliefs, and objects that embody the most broadly shared meanings of a social system. It includes media objects, entertainment and leisure, fashion and trends, and linguistic conventions, among other things. Popular culture is usually associated with either mass culture or folk culture, and differentiated from high culture and various institutional cultures (political culture, educational culture, legal culture, etc.).People who don’t like pop culture (mass culture) tend to forget that it all means something. Hence, it has value whether one likes it or not. It’s not just entertainment. It’s never just entertainment.

There are two things we overlook when thinking about our pop culture loves. First, when we find ourselves liking something, we forget to explore why and assume that it’s good because we like it. Second, we fail to genuinely understand what appeals to other people in things they like that we don’t, and assume something must be bad if we don’t like it.

There’s a third thing, too: we tend to confuse the good with the valuable (as Daniel Blackaby pointed out in a recent Overthinkers episode). Every contribution to pop culture has value. Each cultural artifact (and our response to it) tells us something about our collective selves—about the culture of a people who are a shadow of divine imagery. A bad cultural artifact still has value.

Keep that in mind.

the fundamentalists were right

You’ve heard of (or known) people against dancing, or drums in church, or television and radio. (I’ve known some who oppose the internet.) Every technological development, every introduction of the unknown, has its detractors. By some accounts, Socrates thought writing knowledge down was a bad idea. Centuries later, many church heads opposed Gutenberg’s printing press. Today, social media, artificial intelligence, and augmented reality attract similar opposition.

Reasons for this opposition certainly vary. But the most insidious effect of techno-media developments has gone mainly overlooked, partly because we’ve only been recently able to study them. Evidence shows that particular cultural content (say, a movie or song lyrics) might or might not have a specific effect, but participation in the medium that delivers that content (say, the theater screen or Spotify app) certainly does. To use a differen analogy: there’s not much functional difference between, say, salsa dancing and the country two-step (the content), but dancing with other people (the medium) has been proven to strengthen communal bonds and increase pain tolerance.

When it comes to pop culture—which is increasingly mediated via the internet and technology—it isn’t only the content that transforms us, but the medium and the act of participation itself. As Nicholas Carr writes in The Shallows: What the Internet is Doing to Our Brains:

…in the long run a medium’s content matters less than the medium itself in influencing how we think and act. As our window onto the world, and onto ourselves, a popular medium molds what we see and how we see it—and eventually, if we use it enough, it changes who we are, as individuals and as a society.

In his seminal and prophetic work, Understanding Media, Marshall McLuhan said, “The effects of technology do not occur at the level of opinions or concepts.” Instead, they alter “patterns of perception steadily and without any resistance.”

Perhaps the fundamentalists were right to be concerned that television—or radio, or the internet, or dancing!—would turns us all into the devil’s children. Of course, most of us rationalize that the technology (the medium) itself isn’t evil, that what we do with it is what matters. I’m inclined to agree. Except…

being wary of the medium

“I think, therefore I am” is Descartes’ defining philosophical maxim. But he’d have been even more accurate if he’d continued with: I am what I think. And further: I am what I think of.3 I am turned into the image of my mind.

Studies show that our brains are not just depositories for information and muscles for analysis. Rather, they are the matter through which the rest of our lives are shaped. “As a man thinks…so is he.”4

An experiment conducted by Harvard neurology professor Alvaro Pascual-Leone examined brain changes in people learning how to play a melody on the piano. Two groups were set up: one learned to play by practicing on a piano; the other group sat in front of a piano and imagined playing the melody without ever touching the keys. Carr reports:

[Pascual-Leone] found that the people who had only imagined playing the notes exhibited precisely the same changes in their brains as those who had actually pressed the keys. Their brains had changed in response to actions that took place purely in their imagination—in response, that is, to their thoughts.

Descartes may have been wrong about dualism, but he appears to have been correct in believing that our thoughts can exert a physical influence on, or at least cause a physical reaction in, our brains. We become, neurologically, what we think.

Numerous studies have turned up similar results: “purely mental activity can also alter our neural circuitry.”

What does all that have to do with my love for pop culture?

We engage with pop culture mainly on a mental and imaginatory level. We watch movies, listen to music, and view images—all participations in subcreation rendered within our minds. We receive, interpret, store, and access the content while slowly being warped by the mediums through which that content is delivered.

Thus, we ask: Is headphone culture a marker of the increasingly isolated individual? Is streaming culture partly to blame for a much-observed disruption of communal fraternity? Social networks certainly bear a considerable slice of the blame-cake.

The question: Are our brains—and therefore ourselves—being changed by media and the pop culture which media bears forth?

The answer: undoubtedly, yes.

Whether this is objectively bad in the long run remains to be seen—the marvels of techno-media certainly have their positives and pop culture has its pleasures—but I think the needle leans heavily to negation.

attending wisely to culture

All that being said, I still love pop culture—the actual stuff that makes it up: the books, movies, video essays, music, and podcasts. But I love the media part of it too, the technology that makes it happen—computers and networks, soundboards and graphic design software, the lights, cameras, and action.

When I open Spotify to play a new Weeknd song, I submit to both the content and the medium via which it’s delivered. I’m opening the floodgates of neuroplasticity, especially if I do this habitually. (And I do.)

Neuroplasticity is “the lifelong capacity of the brain to change and rewire itself in response to the stimulation of learning and experience.”5 It is the now-dominant view among neurologists who don’t see the mind as a traditional server bank, a room full of machines that read, write, and access static data. Rather, our minds are more like the cloud, malleable and nebulous, able to warp and adapt in response to various inputs.

The neuroplasticity of the brain is both good news and bad news; it echoes the biblical injunction to “be transformed by the renewing of our minds.” Not only can we change our minds by making different decisions and adopting different beliefs, but we can transform our minds—convert the very function of the matter of the brain—such that we will think differently and live differently as well.

Carr explains:

Although neuroplasticity provides an escape from genetic determinism, a loophole for free thought and free will, it also imposes its own form of determinism on our behavior… The chemically triggered synapses that link our neurons program us, in effect, to want to keep exercising the circuits they’ve formed. Once we’ve wired new circuitry in our brain… “we long to keep it activated.”

It comes as no surprise that neuroplasticity has been linked to mental afflictions ranging from depression to obsessive-compulsive disorder to tinnitus. The more a sufferer concentrates on his symptoms, the deeper those symptoms are etched into his neural circuits. In the worst cases, the mind essentially trains itself to be sick. Many addictions, too, are reinforced by the strengthening of plastic pathways in the brain.

The content and media to which we submit our brains strengthens plastic pathways of some sort. How then can I love pop culture? How can I love the mediums and technologies that undergird our age of information and entertainment? Might that love extend to the possibilities that artificial intelligence has foisted upon us for good or ill?

The first step to answering these questions is being aware that these forces are acting upon us. I’d love to blindly enjoy cultural offerings, but I know the culture is neither entirely innocuous nor benign. It does affect me. And the internet, apps, streaming services, my phone, and other media tug at the plastic of my brain, tempting my attention span to ever shorter dimensions and reinforcing barriers between myself and others I ought to treat as neighbors.

Loving pop culture is no evil as long as we don’t love it ultimately. But I’m guarded against my mind being made into the image of the culture or after the likeness of the media by which the culture is delivered. Awareness is the first step, I know, but what’s the second?

asides + signal boosts

While we’re on pop culture, I might as well shout out some of the cultural artifacts I’m enjoying (or hoping to enjoy).

I’m not sure how The Book of Clarence hasn’t been on my radar until exactly yesterday, but I’m looking forward to this inventive (and fictional!) tale of an ordinary man in the A.D. 30s who glimpses the budding potential of the rising Messiah and tries to ride the wave to his own fame and power.

If songs are cultural indicators, they’re indicating that our culture is getting sadder, especially among younger set. “I’m told that the top search term at Spotify among teens is sad,”

writes.Even the candidates for song of the summer are filled with quiet despair—so much so that Spotify declared it the “bummer summer.” Feeding the trend, the platform serves up countless sad playlists.

There’s much to be said about why this is bad—and why we are feeding the loop of sadness (I say this as someone who collaborated with a friend on a “sad vibes” playlist years ago. Yes, it’s private. No, I’m not sharing it.)

(And, if you’re interested in consistently excellent and insightful analysis of cultural trends, subscribe to

.)Follow Emma Kennedy on IG (@elphinekennedy)! Her weekly Bible non-quotes are hilarious. Like this one:

Happy Fall! (Fortunate Fall!)

One of them anyway.

We use this term fully aware that tens of millions have never seen a MCU movie or think Beyoncé is over rated. So.

[in the sense of meditate on or attend to with my powers of apprehension]

Proverbs 23:7

An excellent summary of neuroplasticity, https://www.physio-pedia.com/Neuroplasticity

Well put! The answer to your final question is probably to cultivate good taste. Even in the realm of pop culture there is good and there is bad—just like in the realm of high culture. And good taste can certainly be helped along by our becoming familiar with how pop culture gets its messages across; therefore, studying the forms, styles, and structures of pop culture is as rewarding and valuable a study as the study of fine art or literature. I don't mean this in the postmodern sense of "everything is equally valid and there are no absolutes"; I mean that the arena for finding value is a lot broader than the guardians of high culture would have us believe.