This is Hazel. She’s eighteen months old. And she’s already found her passion.

I met her while sitting with friends in Edinburgh’s St. James’ Quarter. A couple of our buddies had gotten carried away in the mall, so while we waited on them to divorce themselves from the evils of commercialism, we perched on the steps outside and enjoyed the uncommonly sunny April day. One of my friends had brought her skateboard; I hopped on it and glided1, tentatively, a few paces across the pavement.

On the way back, I noticed a tiny, chocolate-smeared face frozen in fascination.

“I think she wants this skateboard,” I said to the woman who appeared to be the little girl's mother.

“Yes, she’s been obsessed with them ever since we went to Portugal and watched skateboarders perform at a festival.” She cooed at the girl while dabbing at the brown spots smeared Joker-like at the corners of her lips. “Hazel, say hi.”

But Hazel only had eyes for the skateboard in my hands. I offered it to her. Her gaze lit with furious intent and unabashed captivation. A keen, precise pleasure. The pleasure of curiosity in action.

She tugged at the skateboard and pushed it. It was bigger than her—longer than she was tall and heavier. She wrestled with it and sat on it. Lay on the pavement and peered beneath its tiny wheels. She probably would have tried to put it in her mouth if it were small enough.

Finally, her father, a quiet-faced Englishman, offered his hands. She gripped his fingers for balance, planted her tiny feet on the board, and coasted back and forth along a small area of the pavement. She did this over and over, back and forth, never tiring, oblivious to everything except her own glee.

“It seems she’s found the thing she loves already,” I said. “That’s such a blessing at such a young age.” I meant that only half-jokingly.

Her mother, who alternated speaking to Hazel in French and English, agreed.

“I don’t feel like children are empty and need to be filled,” she told me. “They are already full.”

I keep thinking about Hazel’s unbridled fascination with something she can’t possibly understand. Born into a world of machines, she’s found one as beautiful to her as a brightly-colored flower is to a hummingbird. Maybe she will grow out of it. But not if she’s left to her own devices. She’ll be like Chesterton’s child-god, having the “eternal appetite of infancy.” She’ll grow up to describe herself as a skateboarder.

And that is a good thing: to discover what one loves and throw one’s self into it. I say discover, not find—because we don’t find purpose or passion. We get lost in discovering it, and find that it is a thing prepared for us. A thing complete and whole and worthy of exploration. A thing that holds our attention and our frustration—a maze with endless paths in the sky, a source of endless fascination.

I keep thinking about the parenting philosophy of Hazel’s mom too: we don't come into the world empty. We come into the world full. And the world connives to tell us that we are incomplete, that we need stuff and must do things in order to arrive. We are told to grind, as if grinding will ward off “the slings and arrows of outrageous fortune.”2

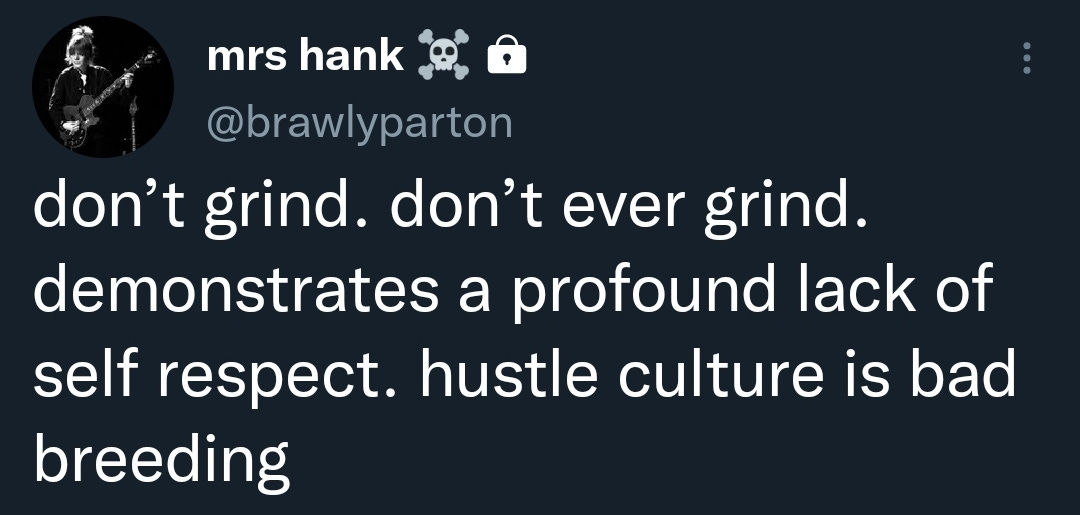

Hazel, don’t ever grind (to quote a saintly Twitter menace).

To be is enough.

We don’t act in order to be; we act because we are. And to answer Hamlet’s question: it is better to be.

We are an act of God. We exist because he exists. We are full beings issued from fullness itself. We have good breeding.

signal boosts

I’m going to start this section now, recommending things I’ve lately been reading, watching, or listening to that I think you should be obsessed with (at least a little bit).

First, this article: The Unpleasantries of Embodiment, by Brian Volck (Image Journal). It’s not that new, but it’s something I keep thinking of and returning to amid recurring discussions about art, what makes it good or bad, and why we get mad at particular deviations of art that stray from interpretations that we’re comfortable with.

The last time looking at it (this week), these lines from “Piss Christ,” a poem quoted by the author, jumped out.

We have grown used to beauty without horror.

We have grown used to useless beauty.

Then, there’s this: Deconstruction Enters Its Flop Era, by Tyler Huckabee over on clusterhuck. (Tyler is, of late, the former senior editor of Relevant Magazine, and clusterhuck is his new thing. If you’re interested in the intersection of faith and culture, go subscribe!) He puts into precise words some of the more complicated feelings surrounding Deconstruction, as the movement/trend is starting to be critically observed by people who have participated in it. I am particularly beholden to his introduction of the term “spiritual editing,” a far more accurate (and less dramatic) way to describe deconstruction that seems more true to what people like myself have been up to.

I could go on. But I’ll end with this: as much as I love like (find interesting?) Rings of Power, it does have its flaws. And some of them are, arguably, pretty big flaws. All the show’s major crimes are recounted in Ben Reinhard’s Crisis Magazine review, There and Back Again: A Rings of Power Postmortem. Check it out if you want reasons to continue bashing the show.

I’m not a skateboarder. I don’t know if gliding, or any other terms related to riding on a skateboard, are actually used by skateboarders.

William Shakespeare, Hamlet, Act 3