rehabbing Santa Claus, or the myth that got away

Why I came to love a Christmas movie I thought I'd hate. Plus, a liturgy for light-hanging. Spoilers, duh!

A few weekends ago, I saw a movie that I wouldn’t have gone to see under ordinary circumstances. I don’t go for films that are ostensibly about Christmas—much less Santa Claus. But people I like invited me to see Violent Night on release day, so I went. At least it’ll give my brain a much-needed break from these term papers, I thought.

I don’t know if I’ll go so far as to say I liked Violent Night. It’s about Christmas and it’s very bloody. It lives up to its title. And it’s funny too—especially if you like laughing at the incomprehensibly grotesque ways movie-makers find for people to die. It’s action-gore-comedy to the max, easy to dismiss as a popcorn flick, fun and forgettable.

But as I sat in the theater, I started to think (against my will), oh, wait, this movie is doing something really interesting. And if I say something’s interesting, I mean it made me think. And I like things that make me think. So, yeah, I guess I liked Violent Night.

But, first, the story, as best I can remember it.

Santa Claus (played by max-dad-bod David Harbour) is discouraged and overworked as he delivers gifts to ungrateful children who don’t really believe in him—and takes advantage of the homes of people who keep up the pretense of faith in his jolly existence. Meanwhile, Jason unites with his daughter Trudy and estranged wife Linda on the way to his mom’s home-slash-mansion-compound in Connecticut to celebrate the real reason for the season: family (or something). Jason’s mom Gertrude is selfish, bitchy, and rich. Like, incredibly rich. She has $300 million stashed in a vault in the family mansion and she plans on being stingy with it.

To make a long story short—this silly movie lasts for two hours—a group of mercenaries infiltrate/invade the mansion, kill Gertrude’s servants, take the family (including Jason’s sister, her son, and boyfriend) hostage, and demand access to the vault on Christmas Eve night. Santa, of course, happens to be on Gertrude’s roof, about to slide down the chimney and drop off some gifts. While the family members beg for mercy—some snootily, some sincerely—Santa stumbles into the fray and (eventually) lays waste to the mercenaries.1

christmas magic

Violent Night takes magic seriously, and that’s something I appreciate. There’s no winking or snickering at the mysteries surrounding Santa, who admits, on numerous occasions, that he doesn’t really understand how “Christmas magic” works even though he uses it for his yearly hustle.

What’s the magic we’re talking about? First, to get up chimneys after he’s climbed down them, Santa pinches the bridge of his nose or snaps his fingers (or something), and there are sparks, and he wooshes up whatever chimney is at hand. This is useful for getting away from mercenaries with machine guns.

The reindeer, of course, are magical because they fly. And sometimes they soar off without Santa, leaving him to deal with the bad guys all alone. By the way, Harbour isn’t portraying good Saint Nick in this film. He’s a drinking, belching sluggard who’d have run away from Gertrude’s compound at the first sign of trouble and left the family to fend for themselves. Honestly, they deserve that. But I’m getting ahead of myself.

Oh, what else? Santa’s magic scroll tells him who’s been naughty or nice throughout the year. It tells a lot more too, like what exactly it is you’ve done. This was one of my favorite features, Santa's very own judgment day tome!2

Then there’s Santa’s bottomless sack of presents which is the sort of sense-making magic3 that explains how he carries gifts for millions of children without making return trips to the North Pole (or wherever he lives). The old man sticks his hand in and out comes the intended gift. There’s not actually anything in the sack. I don’t know if it’s been explained this way before, but it was my first time coming across it. (Then, again, I don’t watch Christmas/Santa movies ever.)

And, finally, there’s the Christmas magic that’s kept our Santa alive for over 1,100 years. This magic isn’t fully explained. But it is real.

The magic of Violent Night is what historical fantasy writer Suzannah Rowntree lately called “soft magic”—it’s “meaningful, symbolic, applicable, and mysterious.” It’s mythic. But it’s employed in a story that doesn’t deserve it.

the myth that got away

I’m no Santa scholar but, as far as I can tell, the popular perception of the white-bearded, twinkle-eyed man in a red, fur-trimmed suit ho-ho-ho-ing his way thru the holidays lacks any serious foundational basis. Not Santa himself—belief in him. It makes one wonder why 1-in-5 American adults believe he’s real, and why the majority of American children eight and under believe the same. What’s more: of adults who no longer believe Santa is real, but used to, one-third of them wish they still believed. Young children prove extremely versatile at deciding when to believe something; how they come to faith in Santa is a keen process.4

Where I grew up, the myth of Santa was, at best, a foolish harmless tale and, at worst, an evil secular story crafted to take the glory of Christmas away from Jesus. But Santa, as we know him today, is neither benign nor satanic. Instead, the jolly gift-bringer is a rootless myth, a symbol with no referent. Perhaps, divorced from Nicklausian legend, it’s fair to say Santa Claus is an empty symbol, its biggest contribution to society being the idea that children should behave and try to get on the nice list. (Research shows it doesn’t have this effect, according to parents.)

But Santa Claus is shorthand with no arm, no body to which it’s attached. It’s the myth that got away. And, in its current state, it contributes to the hollowness of the commercial Christmas celebration. For many, it’s a season with no discernible reason.

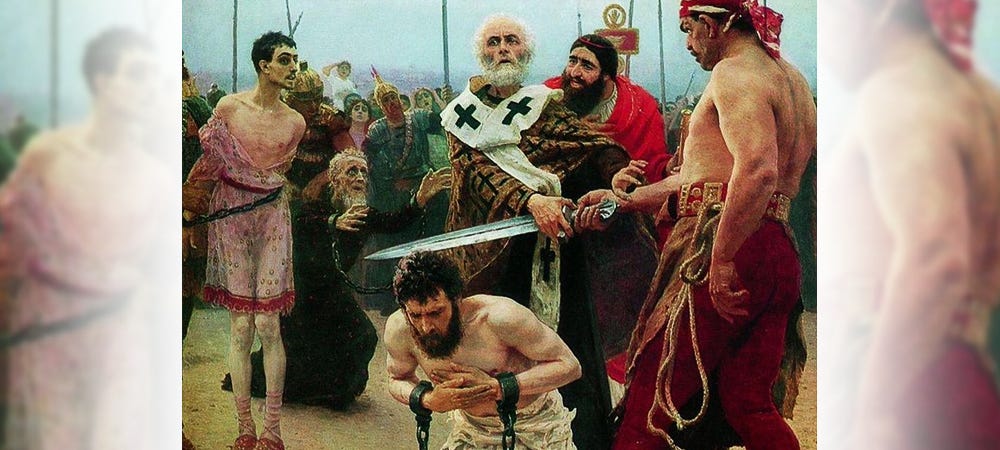

However, as just a bit of research will uncover, the creation we casually refer to as Santa in the West is connected, at least tangentially, to distant origin stories. And like all proper myths, those origin stories are elastic and amalgamated, beginning with the fourth-century bishop Nicholas of Myra who dropped bags of gold in girls’ windows so they’d have money for a proper dowry and not turn to prostitution for survival. Nicholas was a wild and holy guy: he raised children from the dead, slapped a heretic, and exorcised a tree. Allegedly. He earned himself the feast day of December 6th when, from the Middle Ages on, children were given gifts.

Enter the Reformation: Martin Luther puts a Protestant twist on the December 6th tradition, encouraging the act of gift-giving to take place on December 24th or 25th in association with Christmas instead. And who is responsible for the giving of these gifts in Luther’s propaganda? The Christkind (Jesus-kid), already a popular gift-giving figure in some European countries. Now adults began telling children that the baby (or boy) Jesus was giving them toys and sweets and such. This is fine.

Lord Christmas (later known as Father Christmas), the British personification of the holiday itself, first became apparent in 15th-century plays and literature. This figure, too, was forged in the fires of religious conflict as England’s Puritan leaders banned Christmas celebrations which they viewed as Roman Catholic rubbish. (They even tried to get rid of Easter!) So British pamphleteers chinned-up, and in their protest literature adopted Father Christmas as a reminder of the days of feasting and good cheer.

Fast forward a few hundred years to when this chimerical creature (Saint Nicholas-Christkind-Father Christmas) leaped across the Atlantic in the nineteenth century: the beast molted, fell apart, and started recollecting itself into the monstrosity we know today. Dutch immigrants contributed the moniker Sinterklaas (a derivative of Saint Nicholas), and American artists and writers went wild with their depictions of the Christmas guy. And the rest is history.

Voilà! Santa Claus.

Except the real history is forgotten, at least in public, which brings me back to Violent Night and why I came to appreciate the film in the end.

santa has no shadow

Someone once called me a “movie snob,”5 and I’ll indulge that criticism. I like movies that raise big questions and deliver complicated answers, movies that needle the psyche and operate as sandboxes in which existential examinations play out.6 Going in, I just couldn’t see Violent Night turning out to be that kind of film.

And then the little girl Trudy gets a walkie-talkie through which (her father Jason tells her) she can talk directly to Santa Claus. Of course, she can’t, but she believes she can. Her faith is strong until, faced by inquiring mercenaries, Jason insists she’s not talking to anyone and is just pretending and that Santa isn’t real. Feeling betrayed, Trudy runs off with her walkie-talkie. And then Santa, who’s off fighting for his life somewhere else in the compound, rips a radio off a dead mercenary, fumbles with the dial, and he and Trudy do talk to each other. This is a sudden joyous turn. And while my friend is cringing in her seat, hiding her face in her hands—the violence is really violent—I am cheering inside because now we’ve landed on the plane of faith in a thing hoped for despite all evidence being invisible until now. (I could go on about this, but then I'd spoil the even more joyous turn that comes later.)

But I am still worried about the character of Santa. Thus far, in the film, he is an unrooted creature. He casts no illumination on the past and no shadow over the future. Whence comes his Santaness? Is he some product of the amalgam of legends and propaganda mentioned above? Is he good Saint Nick himself? What is the referent of this symbol?

The creators of Violent Night felt this tension too. My guess is they realized their version of Santa was empty without this sort of thing. So they reached into their bottomless sack and pulled out a backstory for Harbour’s iteration of the Lord of Christmas. The Santa of Violent Night is the ancient Viking warrior Nikamund the Red who dealt death and vengeance on the battlefield. He died in war7 and, um, that’s it—oh, he also had a hammer. It was his favorite weapon.

It’s not much of a story, honestly, but it has potential as the sort of myth from which other stories spring. (Think of the mythic Arthur and his scant and scarcely-founded origins.) And it’s the sort of thing people want more of, according to the writers of Violent Night. They told SyFy:

Based on reactions to the first movie on Twitter and stuff, we see a lot of people wanting to know more about Santa’s backstory. So it does feel like there’s an appetite for more of that tale to be told.

The writers, Pat Casey and John Miller, apparently had more backstory that got cut from their original plans for the film. But without the glimpse of Nikamund the Red, a mortal man, his face streaked in dirt and blood—his resurrection and perpetuation by Christmas magic implied more than stated—Violent Night would have been a poorer movie. It isn’t going to win any Oscars or Academy Awards—there’s no auteurism here; it’s Michael Bay on a small scale. Still, the creators demonstrate what, according to Philip Ball, some of the great science fiction writers of the recent past understood: “art doesn’t need a refined surface to reach deep levels of human experience.” Scrappy, unvarnished tales often have the best mythic tendencies.

what do you tell your children?

Myths make space for meaning to rise. The Santa creature, divorced from its mythic origins, holds little room for deeper meaning. But when we know the backstory, when we hold it ready in the murky depths of our minds, the simplistic character of Santa Claus becomes a powerful conveyor of significance and substance. It becomes like a cross dangling from one’s neck. There is something infinitely bigger within the symbol than the symbol, taken on its own, might suggest.

Sure, some will occupy themselves with whether it’s right for parents to lie to their children. And if you’re telling yours that a man sneaks into your house and deposits gifts under a tree on Christmas Eve—and that’s all you’re telling them—then it is a lie and a disservice. But if you are also telling them the stories of the saint who fought and gave and bled, the Child who was given to bleed and die, the communal value of feasting and good cheer, the Judgment when the books of all our deeds will be opened, and the Father of Lights who showers good and perfect gifts on his creation, then Santa is not a symbol unrooted and isolated. He is a symbol that points to its many referents—a symbol with meaning beyond mere material apprehension.

Santa is one of the few still-popular mythical characters whose origins we can be certain of. His story has potential that surpasses the status of a fairy tale for young children, an arm-twister to get them to behave. It points beyond the true-false paradigm and gets at super-truth, the ur-myth.

The question isn’t whether children should be led to believe in Santa Claus. Or whether adults should entertain such beliefs. The question is whether we will recover and maintain the myths and history that justify such beliefs and give them reason for being.

“Work that endures is capable of an infinite and plastic ambiguity; it is all things to all men, like the Apostle; it is a mirror that reflects the reader’s own features and it is also a map of the world.”

asides + signal boosts

On rootedness. I came across this post by Dr. Ragnhild Ljosland which tackles roots (literally) of trees in the great myths. I so wanted to incorporate some of her ponderings into this post, but alas! Go read it in all its glory.

…it is interesting that Saxby raises the question of whether the verse might refer to Odin, Balder or Christ. It is particularly the first two lines that I find fascinating: Nine long hours on the rootless tree hung he there for all to see. What is a rootless tree?Best album + new-to-me artist discovery of the year: Metric. I keep trying to figure out which is my favorite Metric song, but there are roughly five or six that occupy that top-tier space in my head. Metric’s lyrics are plain yet mysterious, and the songs themselves are pretty. Their 2022 release, Formentera, is delicious, but Pagans in Vegas is a good listen too.

A liturgy for light-hanging. It’s much too late for this. If you’re the light-hanging type, I trust you’ve got your lights hung. But at Bible study a few weeks ago, I openly wondered whether there were a liturgy for light-hanging in Douglas McKelvey’s Every Moment Holy. And there isn’t (unless it’s hiding somewhere). So I said I’d write one. And I did. Here it is.

There’s a lot of finer details and threads I’m leaving out so as not to go off on tangents in this post which will be long enough already.

Does Apple have an iScroll yet?

Sort of like how different worlds have different times, so no matter how much time you spend in one world, it takes up none of the time of another world.

Tolkien writes regarding his childhood view of literature in “On Fairy Stories”: “I had no special ‘wish to believe.’ I wanted to know. Belief depended on the way in which stories were presented to me, by older people, or by the authors, or on the inherent tone and quality of the tale. But at no time can I remember that the enjoyment of a story was dependent on belief that such things could happen, or had happened, in ‘real life.’ Fairy-stories were plainly not primarily concerned with possibility, but with desirability. If they awakened desire, satisfying it while often whetting it unbearably, they succeeded.”

She claimed she didn’t “mean that in a bad way.”

Regardless, I really enjoyed the Transformers movies.

I think. This point was murky in the film. I’m assuming he died and was raised by “Christmas magic.” There’s a lot left to the imagination. Which is good! We like imagination.

I like this. It makes me want to rewatch The Santa Claus through the lens of this post to see how hollow or commercial it is