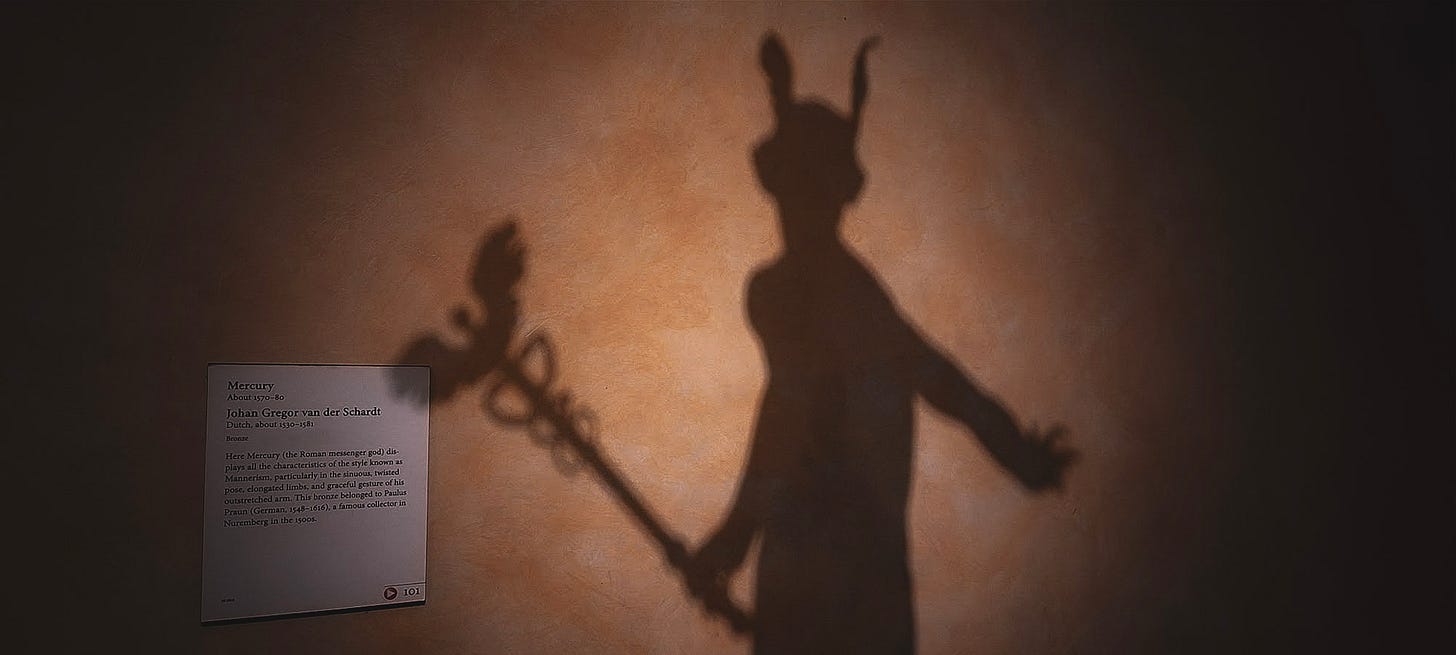

pagan signs on the Christian path

"the supernatural invades the natural all the time, and the natural is the aesthetic of the supernatural"

I’ve got a new essay out in Mere Orthodoxy, in which I examine the resurfacing of pagan sensibilities in the U.S. and England and argue that “the path out of a post-Christian world might well be marked by pagan signs.” The old myths whisper again! And a culture which thought itself sufficiently secular is now lighting candles to forgotten gods! Weaving insights from researchers and thinkers both old and new—Max Weber,

, Chantal Delsol, Francis Spufford, John of Damascus, and (of course) my besties, Lewis and Chesterton—this essay speaks of a growing desire for more than what’s offered by “both wonder-starved religion and an increasingly naturalistic, machine world.”The seed for this piece was planted in the summer of 2022 (if my Notion app notes are to be trusted). A year later, I started drafting under the more enigmatic title, “Little Pagans Everywhere.” The research and writing was so much fun. Almost two years later, here it is! Read the opening below and click-thru to read the rest.

Many thanks… to for challenging me to sharpen the arguments herein, to for talking through these ideas what seems like ages ago and reading and offering thoughts on the first finished version, and to and for offering feedback on a narrative that was originally part of this piece (which I ultimately decided was out of place and gave a home elsewhere). (I feel like I’m missing someone else I owe thanks to… whoever you are, please know you are loved.)

Heathendom came again, the circumspection and the holy fears…

In a 2009 report for The Guardian, writer and broadcaster Cole Moreton speculated that paganism was “beginning to look like” the UK’s “new national faith.” At the time, there were reportedly a quarter of a million people who identified as practicing pagans—more than the number of Buddhists and almost the same as the number of Jews. That’s a massive jump from the 2001 census which recorded only 40,000 pagans in the country. Noting that many won’t call themselves such in front of a government official, The Pagan Federation claims upwards of 360,000 “committed, practising pagans,” making the group the country’s fourth-largest religion.

Across the pond, a similar story of pagan growth is emerging. A 2014 study put the number of “practicing witches” in the U.S. at a possible high of 1.5 million, more than the number of mainline Presbyterians. Two decades after a 1990 CUNY survey found only 8,000 Wicca adherents in the country, the U.S. Census Bureau reported a rise to 342,000. Ten years on, the number of Wiccans has skyrocketed to nearly one million.

Continue with numbers and we’ll soon run into conflicting stats: some surveys rate the number of people turning to paganism drastically higher or drastically lower. The difficulty of landing solid numbers is due to the diversity of flavors that exist under the pagan banner. Some consider paganism “the broadest of churches, spanning witchcraft, Wicca (the organised witchcraft-based religion founded in the 1950s), shamanism, druidry, heathenry and a vast swathe of non-affiliated ‘eclectic’ pagans.” (From here on, we’ll use the term pagan in reference to all the above.)

Data supplies only a skeleton understanding of growing pagan sensibilities in mainstream Western culture. Just as significant are what Moreton calls the “unofficial, instinctive pagans” who celebrate the summer solstice by “going out into the garden at dawn and just tuning in.” Such instinctive paganism is popping up everywhere, from social media’s “witchtok” trend garnering billions of views to the mystical Green Man being featured prominently on invitations to the coronation of King Charles III and Queen Camilla.

Why this enthusiasm? Why now?

Dr. Denise Cush, emeritus professor of religion and education at Bath Spa University, chalks it up largely to the “disenchantment” of the world, something sociologist Max Weber believed was wrought by modernity and the scientific and industrial revolutions. Paganism, she says, “seeks to ‘re-enchant’ the world and restore the sense of awe, wonder and magic.”

Describing the potentiality of a “genuinely post-Christian future” in America, Ross Douthat says the “pagan religious conception” bequeaths to its adherents the understanding that “meaning and morality and metaphysical experience are to be sought in a fuller communion with the immanent world rather than a leap toward the transcendent… [I]t insists that this everyday is divinely endowed and shaped, meaningful and not random, a place where we can truly hope to be at home.”

It’s not all vague transcendence talk, however. Among the monikers used to describe the shift is the pagan-adjacent term nature-based religion. English historian and University of Bristol professor Ronald Hutton says paganism fulfills “a need for a spiritualised natural world in a time of ecological crisis.” Like other religious movements, paganism fills both the spiritual needs of the religiously disenchanted but also a practical, earthbound, social need—like the Black church during the Civil Rights Movement or the current trend that sees Christianity as a “bulwark” against threats to Western culture.

Christian leaders tend to see rising numbers of nonreligious and pagan folks as a cause for mourning, a sign of the decline of Christianity, a rejection of norms established in a Gospel-influenced society, and a regression to say the least. But French philosopher and political theorist Chantal Delsol thinks it is only Christian culture which might be coming to an end, not Christianity itself. In her 2021 book, the title of which translates to The End of the Christian World, she points out that much of the scaffolding of Christendom was raised in reaction to pagan Greco-Roman society and, later, the heathenism of European and Britannic tribes. Reactionary aspects of the faith were then exported to the rest of what would become known as the West. Essentially, the Christianity we know today would not be what it is without paganism. Christianity brought “normative inversion” to pagan Rome, she says, and “what is happening today is an undoing, but it is also a redoing. We are inverting the normative inversion. We are repaganizing.”

This article is excellent and I whole-heartedly agree. I don't think there is nearly enough conversation going on about this topic. I am working on a piece right now about the opportunity Christians have at this moment in history to connect with pagan women specifically (the whole "divine feminine," crystals and astrology culture) through the writings/lives of female Christian mystics... very cool to read that someone else is thinking about this idea. If you have any other authors/thinkers who have written about this recently, I'd love to know! Thanks for sharing :)