Christendom can heal the West, but it can't make us well

Westward leading, still proceeding? The world as end with faith as means.

There’s long been conversation about people who are Christian in name only, folks who claim the faith for its personal and communal benefits—social acceptance, professional amiability, and a perception as an upstanding citizen. But let’s zoom out. Now, people want Christianity not for its own sake, not even for perceived personal benefits, but for the political, cultural, and ideological salvation of America and the West.

Famed British writer and popular atheist Richard Dawkins is the latest to voice this desire. Reportedly startled by lights celebrating Ramadan in England and the number of new mosques under construction in Europe, Dawkins (a New Atheist who describes himself as a “cultural Christian” and a “cultural Anglican”) told an interviewer that he prefers to “live in a culturally Christian country.”

I love hymns and Christmas carols, and I sort of feel at home in the Christian ethos. I feel that we are a Christian country in that sense.

Dawkins is at pains to point out that he is “not a believer” and “there’s a distinction between a believing Christian and a cultural Christian.” Those of us who have heard this talk before are prone to roll our eyes and say, “Well, I guess he can’t help it; Christianity is so attractive. He might as well believe and stop tiptoeing around the cross.” In America, we’ve grown used to politicians citing principles derived from this “Christian ethos” while leaving the question of their own practices up for…well, questioning. So, we shrug (or, at least, I do).

But, of late, a trend is gathering steam. More people, including those who do not see the Gospel as truth per se, now envision Christianity as a bulwark against social and geopolitical trends deemed harmful to the West. A few months ago, activist and social commentator Ayaan Hirsi Ali, formerly a Muslim before turning to atheism, published an essay announcing her embrace of Christianity. The essay focused not primarily on a spiritual transformation but an intellectual one in which she concluded that the best way to fend off threats from ‘China, Russia, Iran,’ “Islamism,” and “woke ideology” is to “uphold the legacy of the Judeo-Christian1 tradition.”

(Pausing here to say I am thoroughly pleased to hear that Ali is attending church and learning more about Christianity. It’s a dangerous thing, opening a door to Christ—he enters. She’s accurately concluded that secularism and atheism are non-answers to a “wilderness of fear and self-doubt” and that Christianity “is a better way to manage the challenges of existence.” But the entanglement of this intensely personal transformation so immediately with public political and social maneuvering is dangerous.)

Dawkins doesn’t want us to be confused! He’s “happy” that “the number of people who actually believe in Christianity is going down” but he “wouldn’t be happy” if England lost all its “Cathedrals and beautiful parish churches” and if people started singing “Non-Existent Being Save the King”2 or whatever. (He’s probably just jealous that atheists don’t have cool aesthetics, inspiring architecture, or sexy, paradox-embracing creeds.) He thinks what Christians believe—the virgin birth, the bodily resurrection of Jesus, the atonement for sin—is actually “pernicious nonsense.” But it’s useful nonsense. And in an uncharacteristic betrayal of reason, he wants the impact of all that nonsense to stick around.

Language like Dawkins’ and conversions like Ali’s are dramatic and draw a lot of attention, but they aren’t the only ones guilty of treating Christianity as a balm for what pains the West. Many believers (especially those in conservative political circles) buy into the same idea: Christianity is not good for its own sake but for defending, preserving, and conserving the nation’s historical status quo. These folks “take an instrumental and political view of Christianity, however well-meaning… [and] sometimes argue that only ‘Judeo-Christian religion’…provides a possible basis for a sound moral life, including the moral basis of national political life.”3

You might be thinking, Daniel, aren’t you a Christian? Don’t you believe that the Gospel is good and its influence can save and preserve good things in the world?

Yes, but that is not what the Gospel is for. Jesus did not come to save (or overthrow) nation-states. He came to save people, sick individuals who need healing, regardless of the nation, state, or political or philosophical system to which they belong. The cross and any associated banners were never meant to be lofted at the head of an army or strung up any palace’s flagpole. Hence the first disciples’ confusion: they expected Jesus to overthrow Rome and establish a Jewish kingdom. He did neither. Crucially, he said, “My kingdom is not of this world.”

This, of course, does not negate Christianity’s outsize social influence. Almost everywhere Christians have gone, they’ve built hospitals and schools, cared for the poor and sick, and influenced positive reform. As a collective social force, Christianity has tremendous power to heal. But when we make paramount Christianity’s influence on the temporal world and its temporary kingdoms, we render the faith a tool to be wielded, and we begin to confuse social transformation and the moral status of a nation-state with individual spiritual transformation.4

When Jesus encountered sick people in first-century Judea, he liked to ask, “Do you want to be made well?” That’s a bizarre question to ask someone who’s ill. But, in the gospel accounts, we find that Jesus was not merely asking if someone wanted to be free of their disease.

In Luke 17, ten lepers beg Jesus to heal them; he tells them, “Go and show yourselves to the priests.” On their way, they are “cleansed” of their disease, but only one turns back to thank Jesus for the miracle. Jesus wonders aloud, “Were not ten cleansed? Where are the nine?” Then he says to the one who returned, “Rise and go your way; your faith has made you well.”

Pay close attention: When the synoptic writers say that Jesus cleansed or healed someone, they often use the Greek word katharizō, which means to purify someone of their physical stains or to cure an illness. Sometimes, Jesus follows up such declarations of physical healing with a statement like “your faith has made you well.” The word well is not the opposite of physical sickness in these cases. It is the Greek word sōzō, meaning to rescue from danger or destruction, to deliver from the penalty of judgment, or to save from the evils which stand in the way of Messianic deliverance. An angel uses the same word when he tells Joseph that Mary “will bear a son, and you shall call his name Jesus, for he will save his people from their sins.”

John uses a different word in his healing accounts—hygiēs, which means to be made whole and is inclusive of being healed of disease. After healing a cripple at the pool of Bethesda, Jesus warns him, “Behold, thou art made whole: sin no more, lest a worse thing come unto thee” (John 5:14). Not only had the man been healed, but he had been made well, saved, delivered from destruction more dangerous than his illness.

The gospels repeatedly indicate this shift from mere physical health to spiritual renewal and a body-soul wholeness. Many benefited only from Jesus’ healing miracles. But some expressed (or were prompted to express) genuine faith in the God who walked incognito. And those people were also made well.

Christianity, no doubt, has a healing impact on society. But its real purpose is to make people well, to make us whole, to deliver us from the destruction of our souls. A world built and maintained by Christian hands might have many hospitals and schools. It might enforce good morality and conduct. It might foster stable families and flourishing businesses. It might heal and preserve the environment in such a manner that even atheists like Dawkins could be grateful. But this is not what Christianity is for. When we neglect this, when we fall in love with the effects of Christianity for their own sake, we have little more than a form of Christendom, a holy empire prone to rot.

History shows what happens when Christianity blends with imperial thinking and the impulse to preserve and expand human ideologies, worldviews, and ways of life: slavery, holy wars, subjugation of the other justified by doctrine, religious infighting backed by state powers. We’ll end up there again if we’re not careful.

I get it. Western civilization, intensely shaped by Christian people, is nostalgic and comfortable. But we mistake familiarity and health for being truly well, and eventually lose sight of the latter all together. In a panel discussion late last year, Ali expressed such faulty logic:

…in the West, we made this mistake of having a debate about is there a God…and then having everybody weigh in and twisting ourselves into pretzels… I’ve come to realize over time: that is a waste of time, it’s not in the least helpful. I think what we should have done instead, what we should do instead, is compare the different concepts of God humanity has come up with, and the different stories that humans have told each other… And what I find appealing, for instance, about the Judeo-Christian story, is that transcendent power ends up being a story about freedom, about tempering power…

In short, Ali believes Christendom, this “Judeo-Christian story,” is the best mythology for the West because it supports our free and democratic experiment. Christianity, ergo Christendom, is something for us. And whatever else it’s good for, it’s mostly good for that.

This reductionist view holds an unspoken attraction. An ideology (such as a democratic republic) devoid of any deeper mythology, subsisting only on excitement and human reason, quickly falters as a guiding light. Ben C. Dunson points out:

…political liberalism has no positive vision for life. It puts forth certain rights: life, liberty, the pursuit of happiness, and so forth. Yet, it is unable to tell you why you should even want to live, what you should desire to be free to do, or how you can find happiness.5

Christianity provides a framework for answers to such vital questions. But Christianity is more than a mere manual for life and will not survive in a culture that treats it as such. Political philosopher Russel Kirk suggested…

…the corpus of English and American laws—for the two arise for the most part from a common root of belief and experience—cannot endure forever unless it is animated by the spirit that moved it in the beginning: that is, by religion…6

Ali correctly assumes that “atheism is too weak and divisive a doctrine to fortify us against our menacing foes”—whatever one thinks those foes are. But Christendom (Christianity solely as cultural and political bulwark) is as well. Don’t get me wrong: I love the Christian aesthetic. I love the progress and sense of morality and justice a true Christian vision brings to the world. I love cathedrals and parish churches and “God Bless America.” The absolute metal realism of God sacrificing himself to himself for the salvation of his creation is unmatched. But the cultural Christian “trivializes Christianity.”7 He makes it less than what it is, taking the art of God and using it as the hammer and sickle of man.

You can have Christendom for only so long before one begins asking why? That’s what’s happening now with progressive liberalism and New Atheism. That’s what happened before with the Enlightenment and the sexual revolution. Societies, having accepted particular mores for so long, begin asking why, and without sufficient answers, they throw off perceived shackles to mixed results.

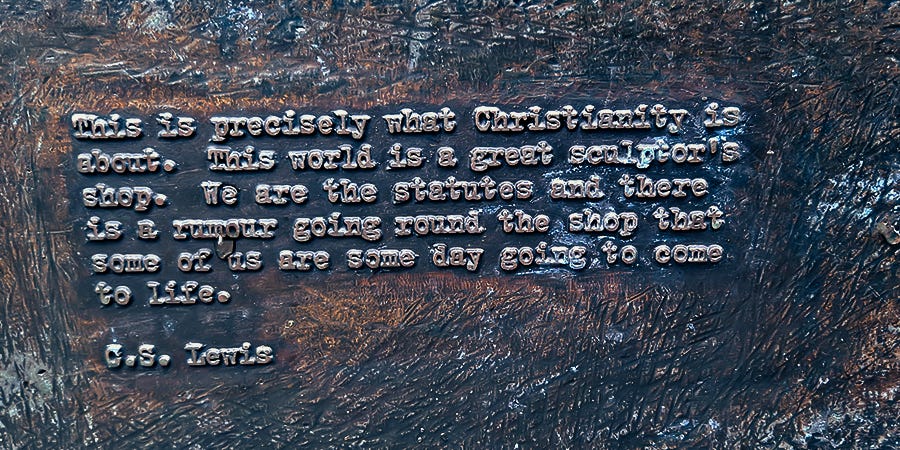

I’m sure not everyone who favors Christianity as cultural bulwark is insincere. Ali strikes me as particularly earnest. Dawkins comes off as a sad, tired nerd putting far too much energy into being Christian while not believing any of it. (James had something to say about double-minded men.) But there’s a slippery slope from being a Christian who loves his country to being a patriot who loves his Christianity for the sake of his country. It’s an old trick, one described by an elder devil to his apprentice and recalled in The Screwtape Letters:

Let him [the Christian] begin by treating the Patriotism or the Pacifism as a part of his religion. Then let him, under the influence of partisan spirit, come to regard it as the most important part. Then quietly and gradually nurse him on to the stage at which the religion becomes merely part of the “cause,” in which Christianity is valued chiefly because of the excellent arguments it can produce in favor of the British war effort or of Pacifism.

Once you have made the World an end, and faith a means, you have almost won your man, and it makes very little difference what kind of worldly end he is pursuing.

Christianity certainly produces excellent arguments which reinforce classically liberal ideals. The Christendom that results from this blend of faith and ideology might indeed heal the West and bolster it against competing worldviews—but only for a time. All kingdoms rise and fall, and the kingdoms of this world, including the anti-Western ones, eventually become the kingdoms of Christ. That’s rather inconvenient for Richard Dawkins. And it’ll be pretty uncomfortable for those of us who cling to a cozy, convenient Christendom instead of Christ himself.

asides + signal boosts

There’s plenty of balanced commentary out there that rounds out the discussion we're having here. I encourage you to find and read some of it. But as a gateway, check out

’ leading remarks in ’s latest newsletter. At least read down to the part where she starts talking about Shakespeare. You’ll see what I mean.I’m almost finished watching Hulu’s The Other Black Girl, a curious, trippy exploration of race, power, and influence within the tight confines of a (fictional) publishing company. It’s a slow burn, but the episodes are short and the twists are satisfying. Plus, Erin McCormack delivers a spotless, ingenuous performance as Richard Wagner.

Highly recommend

’s essay Would We All Be Happier as Tradwives?, not because I think I’d be happier as a tradwife, but because it’s a pointed, snazzy discussion about the difference between aesthetic and reality, between social expectations reinforced by social media and the diverse array of individual life paths. I love it.The term “Judeo-Christian” is, of course, questionable and problematic, but it does mean something to the people who use it, so it can’t be simply discarded.

I just made up that title. I don’t really know what atheists say at Coronations. They probably don’t even have hymns.

Kevin D. Williamson, Who Are These ‘Cultural Christians’?, The Dispatch, https://thedispatch.com/newsletter/wanderland/who-are-these-cultural-christians/

A Ten Commandments display at the state courthouse says little about the moral status of the people in that state. (Although it says a lot about who has political power in that state.) And it is just as likely a pretty tombstone as an indicator of anything real—and we know how Jesus felt about pretty tombstones.

Ben C. Dunson, Richard Dawkins’ Cultural Christianity, American Reformer, https://americanreformer.org/2024/04/richard-dawkins-cultural-christianity/

Russell Kirk, We Cannot Separate Christian Morals and the Rule of Law, Imprimis, https://imprimis.hillsdale.edu/we-cannot-separate-christian-morals-and-the-rule-of-law/

Kevin D. Williamson, Who Are These ‘Cultural Christians’?, The Dispatch, https://thedispatch.com/newsletter/wanderland/who-are-these-cultural-christians/