Marcus Aurelius is not your savior

Tackling the crisis of uniquely uninspiring men

Dude, being a man used to be so easy! But now it feels messy, complicated, and sometimes dangerous merely existing as male. If you haven’t noticed, people are asking questions like, what’s the matter with men? and are men necessary? Others eagerly proclaim men are trash and masculinity (an attribute of maleness) is toxic. Many suspects led to this crisis of male existence and the symptoms affect multiple generations.

Men, from their teens to their forties, seem to be receding into a whirlpool of video games and pornography. We’re getting three college degrees for every four that women earn. Anecdotally and statistically, men have trouble merely talking to the opposite sex. (If I had a dollar for every time a young man has told me, “Women are scary…”) Numbers show that only half of single men in their twenties and thirties are actively pursuing a romantic relationship. Underlying all of this is the general malaise that men are lost, listless, in their “flop era,” meandering aimlessly through life with no sense of who they are. Men are “less interesting than they used to be,” someone remarked on Twitter.

Sadly, men also account for 75% of all “deaths of despair” (by suicide or overdose).

Some will call this flurry of concern about men overblown, a recoil from the tremendous social shifts that brought more equality for the fairer sex in private and public life. Half of women today earn the same or more than their husbands. The leveling of educational, employment, and economic playing fields has, for many women, rendered finding a husband for stability’s sake less necessary and, very often, an inconvenient entanglement.

Plenty of concern over the wellbeing of men gets handwaved because—well, the patriarchy. (Men have had it easy for millennia! Etc.) And, yes, entrenched maleness within institutions and societal structures is present to this day, but most men don’t live under a patriarchal aegis. Most men aren’t governors or senators or pastors or professors or C-suite occupiers. Most men are likely to hear “men are trash” every day and tacitly agree with it because, oh well, there’s no advantage in saying anything to the contrary.

So, what happens when men are told they’re trash? (And more to the point: when men feel like trash, exhausted and disillusioned?) Someone’s got to take the trash out.

We live in an era of boys cosplaying at manhood. We’ve gone upstairs, rummaged through the attic, and come down with various costumes, unsure of which one to wear for the stage play. The script is confusing. Our lines are given to us, then yanked away. Now the curtain’s raised and we’re caught hopping around with our clothes halfway on. No one can tell who we’re supposed to be playing, least of all ourselves.

Deciding to be a man (or type of man) is not a terribly novel problem. Concerns over how boys arrive at manhood have been raised before, especially in old America. Nineteenth-century writer Washington Irving advised the country’s upper class to send their boys to the frontier to earn their “manliness” instead of sending them to Europe where they would grow “effeminate” lounging around in Parisian institutions.

Speaking of America, I don’t like how so much of the conversation about manhood these days is framed in political terms—left, right, conservative, liberal, etc. In the past few months, much of what I’ve read or listened to while planning to write this post casts men as pawns, electoral fodder, and social stratification brackets, only as good as the agendas they support and the points a political party can score with or without them. If you’re a concerned citizen despairing over our national electoral choice this year, you can understand male helplessness.

Contributing to the sense of helplessness is the general reluctance people have toward outright trying to help men. To go against the grain and say men, in general, need help—or at least that male concerns deserve discussion—is to risk the wrath of the self-established anti-establishment social outrage crowd.

We may not entirely grasp what’s underlying the manhood crisis—it’ll likely be generations yonder when that’s figured out—but we know something’s wrong. Men today are like leaves before a hurricane. Some of us are aware of it and some of us aren’t. We’re searching for definition, for the contours of our creaturely design. This aesthetic territory has become the battlefield for the soul of manhood. The players on this field are numerous and intertwined. They include Andrew Tate1, Jordan Peterson, the so-called “Bronze Age Pervert,” whoever is running Promise Keepers right now, every know-it-all talking about manhood, and all the ladies who repost “men what’s stopping you from looking like this” memes or laugh-cry about going to dinner with all their successful lady friends and not a marriage ring in sight.

And then there’s my underplayed favorite, Marcus Aurelius. The Stoic philosopher and late Roman emperor doesn’t get enough attention in this conversation despite his ideas being the seed for where much of the conversation has gone. I know more men who read, quote, and repost IG quotes from Marcus’ Meditations than any other book. (Yes, I’m calling him Marcus like he’s just a bud.) I suspect they’re searching for something, some rules for life, one might say. (Or maybe this is their way of Always Thinking About the Roman Empire.)

We probably shouldn’t put Peterson, Tate, Promise Keepers, Marcus, and all the rest in the same bucket. But they’re all successfully bullhorning for male attention for a reason. They meet the male demand for both specificity and aspirational visuals.

Along the spectrum of arguments on how to fix generations of uniquely uninspiring men, we have the alt-right, the collection of podcasts, vlogs, and social media commentary that make up the “manosphere,” misguided “biblical manhood” conversations, and your politically liberal and socially areligious “just be a good person” contingent. Unfortunately, a lot of that is laced through with “misogyny masquerading as being simply pro-male, advocating a return to a strict hierarchy in which a particular kind of man deserves to rule over everyone else.”2 All these elements speak to a desire for specificity in what’s expected of men, a desire to eradicate confusion and questions.

However, we’re in a catch-22; such confusion and questions are set to be with us for a while. As doubts about manhood pervade the populace, more boys grow up without fathers and other forms of positive, touchable male leadership. And if the conscientious man-boys wrestling with these questions today don’t figure it out, well, where does that leave our sons and their sons?

We do have plenty of talk about masculinity, but talk is all it is, aimless and nonconsecutive, never the sense of anything developing.3

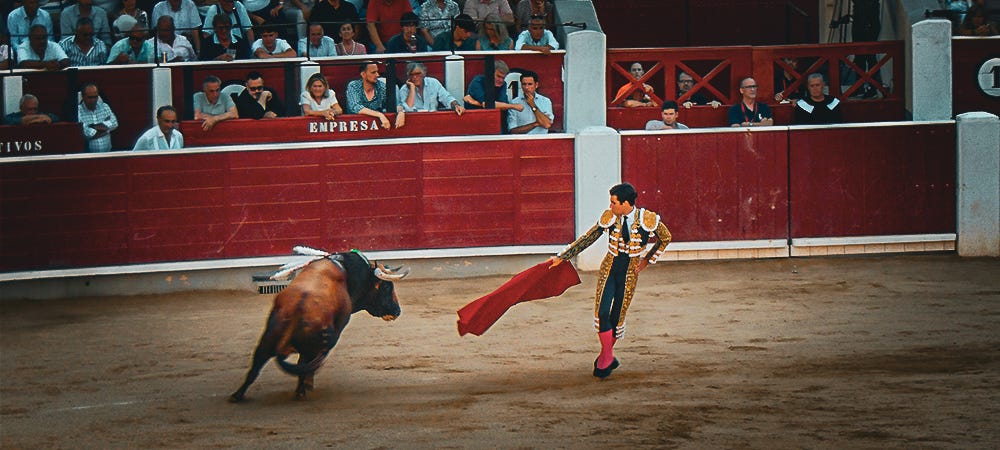

Men are shaped by two things: specificity and visuals. The first comprises a set of rules or acceptable behaviors—this is how a man behaves. The second comprises aspirational images—this is what a man looks like. I’m zeroing in on the former here because it’s where, in my opinion, the more significant problem lies. The second is a far more complicated discussion which, perhaps, I’ll attend another time.

In many ways, men struggling with identity today are simply children who have not grown up. Many have turned in their childish things but have yet to replace those things with the accoutrements of adulthood. Some cling to childish implements because they haven’t yet been presented with suitable replacements and don’t know where to look for them. This is not a crisis of behavior but a crisis of being. Not a matter of what a man is to do but what a man is.

Some might contend it’s simple: every boy becomes a man when he turns eighteen, or loses his virginity, or reaches voting or drinking age. That’s a stunted, one-dimensional view of manhood and adulthood in general. Also, we aren’t simply asking how do we make men? but how do we make good men?

It’s generally accepted that a good man follows rules, a code of honor, and has parameters for his conduct. Some of those parameters control why he doesn’t drink or sleep around or is slow to anger and retaliation and sometimes get him accused of not being man enough.

In an interview, Christine Emba, the Washington Post writer who stirred anew the male crisis pot with her essay last year, describes men as desperately crying, “Give me rules.”

The liberal, progressive answer is: “Lol, no, just be a good person.”

And the male reply: “No, like, actually, Give. Me. Rules.”

Hence the popularity of someone like Jordan Peterson, whose work I have yet to really dive into. Clearly, he’s a polarizing figure: people either love him or hate him. His most popular book has been mocked for its simple statements of advice like, “Stand up straight with your shoulders back.” (You can laugh, but I’ve had to tell one of my subordinates, a young man of nineteen about to turn twenty, to walk with his head up and shoulders back. It makes a difference, and somewhere along the way, he missed that piece of information.) Say what you want, there’s a reason why Peterson’s 12 Rules for Life and Marcus Aurelius’ Meditations hit bestseller lists. Simple rules sometimes need to be restated.

But are there rules specifically for men? This is the harder question because all the rules one might imagine apply to men also apply to women. “Just be a good person” is hard to refute. (By the way, when people say, “just be a good person,” what they really mean is: be just as good as I am but no better and/or you must have the same political and social views as I do because anything outside of that is unacceptable.)

When men ask for rules, we are really saying: what is my role? In the old days, the answer was easy: men wore the mantle of protector, provider, and wilderness guide. Protectors, providers, and guides for who? Their wives, their children, their communities. To suggest such a thing now is to call into question one’s egalitarian bona fides at best or be labeled toxic and chauvinistic at worst. Still…

Being a good person is not a clear enough road map. It’s not a strong enough norm and that’s what young people especially are looking for. I think what it means to be a good person is, in some ways, tied to your embodiment, your human form, as a male person or female person.

Being a good person as a man means asking what you do with the extra natural strength that you have been bequeathed as a man.4

That’s essentially it. To use a remarkably male analogy, a football player isn’t allowed to just be a good football player. He must be a good tight-end, or a good wide receiver, or a good quarterback, or a good kicker. He must be good within the parameters and demands of his specific role. That’s what makes a winning team.

I also like how Caitlin Flanagan puts it:

[There’s an] obdurate fact that exists far beyond the shores of theory and stands on the bedrock of rude truth: Men (as a group and to a significant extent) are larger, faster, and stronger than women. This cannot be disputed, and it cannot be understood as some irrelevancy, because it comes with an obvious moral question that each man must answer for himself: Will he use his strength to dominate the weak, or to protect them?5

The debate over rules and roles is laid to rest on the bed of essentialism. Both men and women are called to protect, but a man in accordance with his nature and a woman in accordance with hers. (And the natures are essentially different; if they weren’t, then they would be the same and we wouldn’t be having this conversation.) The same goes for nurturing and laboring and loving. Both men and women are called to these behaviors, but to the extent to which each is naturally capable (and there is a diverse array of natural capabilities). If this sort of thing makes one recoil, then one has some growing up to do.

A few nights before Christmas two years ago, a friend called me. She was frantic, at the end of her emotions. “I can’t do this anymore,” she said. “I have to move out of my parents’ house.” My friend had been a flight attendant for a luxury airline. Covid cut her out of her job. She moved back home, met a guy, married him, and had a kid.

The guy, her husband, shirked his duties and left his wife and newborn in such a pinch that she had to move back in with her parents, re-opening old, tragic, and dramatic wounds between her and them. Tensions grew to such a point that she believed continuing to try to work things out with her parents was no longer a good idea. Without hesitation, I offered my place as a temporary solution and helped her move in the next day.

Within a week, my YouTube recommendations changed from Batman movie clips, theology lectures, and what’s wrong with Marvel video essays to Bluey and Cocomelon songs. In the evenings, I entertained the adorable 11-month-old so her mother could shower and enjoy much-needed downtime. And when that little girl turned one, her mother and I cobbled together our mutual friends to throw her a party in my kitchen—a party she’ll only know about from the pictures.

I’m no stranger to difficult parental relationships, and some of my friend’s experiences mirrored my own. We spent several emotionally strained hours discussing childhood traumas and how to overcome them.

I relate this experience because, during that time, I felt a keen sense of arrival. A sense that I was doing something I was supposed to and had been meant to do. As far back as I can remember having serious thoughts, I knew the primary thing I wanted when I became an adult—when I became a man—was to be capable of helping the people around me, to be someone others could depend on in their moments of material, emotional, or financial need. I wanted to be true to my word and steadfast, to be reliable and useful. To be a provider and protector.

The sense of arrival I felt then was a sense of arrival as a man. In those moments, I was not a boy, looking upward and outward for aid, but someone whose strength was lent to others. That sense of arrival is important to me.

“…if a new model for masculinity is going to find popular appeal, it will depend on putting the distinctiveness of men to good use in whatever form it comes.”6

There’s nothing unique about my experience. I share it to say that a boy cannot know that he has become a man (or is at least on the right path of manhood) without that sense of arrival, without having crossed some threshold, literal or metaphorical, internal or external. That is why men are turning to Peterson and Tate and Marcus Aurelius. They are asking, How do I know? What must I do? What are the markers? And these men are saying: This is how you know. Here is what you must do. These are the markers.

We need markers, such as they are, in order to recover from the recession in manhood. The path to manhood is not the same for every man—we’re a far cry from the monosocieties of yesterday, after all. Still, there’s something to say for the “vision quests” of Native American tribes, where a boy transitions to manhood by fasting, by solitude, by ceremony. There’s something to say for the ritual passing of responsibility for one’s actions and beliefs from parents to self—responsibility being one of the markers of manhood—which Jewish boys undergo at bar mitzvah. There’s something to say for putting oneself through the rigor and discipline of military service at the start of one’s adulthood, however else one intends to spend their life.

Men (or boys trying to be men) need the opportunity to say they’ve arrived. And this consists of doing just as much as being. Whether the doing is a ritual undertaking or an original one isn’t so important. (But a ritual undertaking takes a lot of the guesswork out of it.) A young man I know plans to hike the Appalachian trail next year, for most people a 5-to-7-month venture covering over 2,190 miles. In some dimension, I’m sure he’ll be more of a man when he finishes than he is now.

Such markers, such rites of passage, such quests in pursuit of manhood are not the whole solution. But they certainly put us on the right path. Do all those boys undergoing bar mitzvah feel startlingly changed after the ceremony? I doubt it. But the intentionality of such acts should not be lost on us. What leads up to and follows such transitional rituals is key: the idea itself sets expectations and says this is the way a man becomes.

Despite claiming he doesn’t hold much with Marcus Aurelius, Jordan Peterson aptly sums up the appeal of the late, great Stoic. Stoicism is a “compensatory fantasy,” the sort of thing people get interested in when popular ideas, after being attempted for a while, become exposed as not all they’re cracked up to be. Marcus Aurelius’ ideas are “exactly the opposite of every philosophy you ever hear about now,” Peterson says. He’s not wrong: there’s plenty of philosophy and life advice going around that’s built on hedonism and feeling-based justifications instead of the logic, discipline, virtue-seeking, and temperance that stoicism is known for.

Finding that the former leaves much to be desired, men seek some semblance of the latter. We’re trying to figure out a healthy version of that. Stoicism is an austere and uncolorful master. It is strong, stark, and courageous—hence the appeal, but there is much to be desired in such a framework.

These rules that men seek, these ways of being, must be enshrined in a larger, better, and valorous tale. Life is more than brute death and glory à la Rome, more than discipline and crude strength. That, by itself, is a recipe for toxic masculinity. If men are truly to arrive, we must bring down more than costumes from the attic. We must figure out a better story to tell and better roles to play—a story that suits our times as the uniquely inspiring men of the past suited theirs.

Take this as the requisite caveat regarding Tate’s crimes. Some would argue that his reported behavior nullifies everything he’s had to say—a lot of it is awful anyway. But he has the ear of a vast swathe of the male population, so.

Christine Emba, “Men are lost. Here’s a map out of the wilderness.” The Washington Post, https://www.washingtonpost.com/opinions/2023/07/10/christine-emba-masculinity-new-model/

Phil Christman, “What Is It Like to Be a Man?” The Hedgehog Review, https://hedgehogreview.com/issues/identitieswhat-are-they-good-for/articles/what-is-it-like-to-be-a-man

Christine Emba, “The new crisis of masculinity,” The Gray Area [PODCAST] with Sean Illing, https://www.vox.com/the-gray-area/23813985/christine-emba-masculinity-the-gray-area

Caitlin Flanagan, “In Praise of Heroic Masculinity,” The Atlantic, https://www.theatlantic.com/ideas/archive/2023/08/heroic-toxic-masculinity-boys/675172/

Christine Emba, “The new crisis of masculinity,” The Gray Area [PODCAST] with Sean Illing, https://www.vox.com/the-gray-area/23813985/christine-emba-masculinity-the-gray-area

I have so many questions on these! Looking forward to more answers f your thoughts