eat me, drink me: aesthetic + the individual as self-curator

From The 1975 to The Horse and His Boy, trading consumption for connection and living beyond the tale we happen to enact

You’re making an aesthetic out of not doing well / And mining all the bits of you you think you can sell.1

Humans are remarkably curatorial beings. We waltz through life sampling food, art, literature, headlines—dumping into our streams of consciousness the things that fit, the things we find attractive, and overlooking the vast interests of others. We’re eclectic beings by default. The fracturing of metanarratives, a phenomenon sped by the incredible democratization of media, has facilitated our ability to curate life.

It was only a matter of time before we’d turn—or realize that we’d turned—our curatorial capabilities on the mess and matter of our existences.

‘a really sinewy line of contortionists’

No single person knows us fully. We hyper-curate our biographies near-effortlessly, angling a story one way when talking to our parents and another when relating it to our gossipy best friend. We post snapshots of reality on social media and recount a vacation's events differently in conversation with co-workers or church family.

A merciless observer might call it lying. And there is an element of dishonesty to it. But the capability to cast the threads of our lives within specific frameworks (defined by audience, setting, or medium) is as beautiful as it is terrifying, and we often do it without being aware of it. Now, however, we cannot help but be aware.

The New Yorker recently published Jia Tolentino’s fascinating feature on Matty Healy, frontman for indie pop-rock band, The 1975. Healy is overly aware of himself as a performer, and him repeatedly squeezing his body through small screenless televisions on stage is a vivid demonstration of his open wrestling with the concept of existence as performance. Many have their eyes on him even when he’s not on stage. He has settled on the understanding that life is “a balance between what is real, what is said, what happens, what people believe, what people project, and what is true.”

We could take that admission apart for decades and still not reach the end of the discussion. Instead, I’ll borrow the words of Healy’s recently rumored paramour:

We know our friend in a certain light, but we don’t know them the way their lover does. Just the way their lover will never know them the same way that you do as their friend. Their mother knows them differently than their roommate, who knows them differently than their colleague. [Etc. Etc.]

We think we know someone, but the truth is that we only know the version of them that they have chosen to show us.

There will be no further explanation.2

Actually, we will attempt further explanation because you and I, like Healy, come from a “really sinewy line of contortionists.” We twist and warp our unfolding biographies into a shape that we think is pleasing, desirable, or useful. We often operate, to borrow Tolentino’s words, like “self-chroniclers gathering material” for our own “devastating pop albums.” At risk of sounding vaguely condemnatory, we end up, as Tim Urban told Bari Weiss, being image-crafters: “presenting a person who is not [us], but who [we] want people to think [we] are.”3

The situation evinces a “gap between reality and a curated reality.”4

image-crafters + imagined lifeworlds

Image-crafting has always been part of the human experience. The people of Babel built a tower as high as heaven to make a name for themselves and Ozymandias raised his image above the land, claiming the title “King of Kings.” Persian emperors took advantage of their kingdoms being divided into smaller and smaller provinces—when they wrote to other kings, they could declare themselves lord of, say, 156 provinces instead of, like, twelve. In later centuries, royalty sat long hours for portraits, carefully placing every detail to indicate wealth, power, intelligence, or holiness.

Today, we can produce hundreds of self-portraits every hour. And some of us do. You ever traveled with someone who wants you to take a hundred pictures of them in the same spot with only slightly moderated poses? I have.

“It’s not about the photograph. It’s about the experience,” I insisted recently in the Silent Quarter of Milan.

“No, it isn’t,” my friend said. “It’s about the photograph.”

“Documenting experience has become synonymous with experience itself.”5 And the way we document our experiences, often adopting the public gaze and refusing to settle unless the finished product is “Instagram-worthy,” forces a separation between the self we are and the self we portray. In the eyes of a viewing audience, we are no longer ourselves. (But they don’t know that!) We’re sending aspects of our lives out into the world for various audiences to face.

“The uploaded self is no longer anywhere else” declares a study on the effects of Instagram use.6 This sounds suspiciously like Jean Baudrillard’s reasoning that reality is dead.

The hyperreality that occurs on Instagram is the effect of diminishing direct interaction between individuals. So that the virtual world or pseudo-reality is considered real. Instagram is not just a representation of human life, but a reality.

When we interact with each other via social platforms, we experience a simulated reality. By reading this substack, whether I intend for you to or not, you gain a perception of my life. An image of me is crafted in your mind. By writing a certain way or about certain things or telling particular stories, I can shape how you see me.

Today, reality is produced. Stylistically. Consistently. Or even haphazardly, but in a carefully haphazard way—a way that we can analyze and pick apart. A way we can effect.

I recently heard an artist describe his desire to make an “authentic” album by keeping mics running through the entire recording process and refusing to edit out the sounds of people walking in and out of the studio, coughing and sneezing, throats clearing, etc. But his desire to produce an authentic work is an aesthetic decision. It’s the manifestation of a lifeworld imagined by the artist.7 He wants us to think a specific thing when we listen to his music, to see him in a specific way. As authentic as the end product may seem, it’s still all about the aesthetic.

When we tell our stories to other people, we take aesthetic threads and spin narrative webs. We take our imagined lifeworlds and manifest them via multiple forms of media—visual, audible, verbal, written, photographic, social. Our imagined lifeworlds are spiced with reality, not the other way around.

is narrativity bad faith?

There’s a scene that haunts me from a novel I read a long time ago. (I’m almost certain it’s one of Judy Blume’s.) In it, a child observes a striking splash of red paint on a white canvas. She wonders why it’s there and what prompted the artist (her father) to make this thing. The answer is given that her father was angry and that this piece of art, this splash of red on white, expresses his violent feelings.

Even that simplistic interpretation invites one into a story: Why is he angry? Who hurt him? Did this art exorcise his feelings? What was he doing before turning to the canvas? What did he do after?

We can’t talk about aesthetic and the individual as self-curator without considering whether we, in fact, cannot help ourselves. We, as a species, are lashed to the mast of narrativity. Our storyboundness is writ large across human experience and in almost all our creations. And that is why it’s impossible to separate a discrete aspect of our lives without portraying it as a narrative or part of a narrative or using it to contribute to a particular aesthetic.

The fact that we edit our incomplete biographies depending on who’s watching is normal. “I take a special pleasure in hearing people relate events from their lives several times,”

writes. “People tend to suit the stories to their audiences, at least if they know them.”8 But some would argue that our narrative tendencies aren’t de facto at all and that our tendency to lean into story isn’t the best way to live.Philosopher Galen Strawson expresses caustic opposition to the “phenomenon of experiencing oneself as a self.”9 He divides humanity into two types of people—Diachronic and Episodic. Diachronics naturally storify their lives. They see themselves as being within a narrative—everything has led up to now—and they are very aware that they think this way. Episodics, on the other hand, live in the moment. They do not consider themselves as existing within a narrative, even a narrative solely concerning themselves. Before and after don’t matter; what matters is the present. The self of yesterday and the potential self of tomorrow are nonexistent.

Strawson considers Diachronics and Episodics to be “radically opposed.” He accepts the argument of Jean-Paul Sartre, who “sees the narrative, story-telling impulse as a defect… He thinks human Narrativity is essentially a matter of bad faith, of radical (and typically irremediable) inauthenticity, rather than as something essential for authenticity.”

I find anti-narrativity, a seemingly growing trend in philosophy and public sociology, troubling on several levels, including very personal ones.10 I disagree with Strawson’s line-drawing between Diachronics and Episodics. Humans are all naturally Diachronic; we like beginnings and endings, knowing where we come from and where we’re going. However, many of us skew Episodic due to life experiences. Trauma forces us to separate certain aspects of our lives from others to protect what is now from what came before. Exile from community, whether forced or willingly taken, can make us feel disconnected from past and future. Use of social media warps our minds to see life as a series of unconnected episodes; we live for the tweet, the perfect snapshot, the 24-hour story.

If diachronicity and narrativity are endemic to the human condition, they cannot be inauthentic—even if some don’t express such tendencies as much as others. The idea of someone being more truly herself because she doesn’t see herself as within some sort of narrative simply isn’t true. One can only be what one is. (And one does not have to be conscious of a narrative to live as if she were within one.)

But to be more than one is? That’s what narrativity allows for, and that’s where aesthetic comes in. We don’t become our biographies—not even the biographies we cast in the curated stories we tell. But if we could—oh, if we could!

Deeply-rooted narrativity explains the trend of people claiming they’re experiencing “canon events”—things that must happen for them to become their future selves. Narrativity, to borrow Charles Taylor’s words, is an ‘inescapable structural requirement of human agency.’ Swanson’s argument ignores that the past and memory shape the present. Take that away and we can’t know who we are. Our present narrativity and self-curation is an effort to shape our stories for today and tomorrow.

feasting on ourselves

even when i am ostensibly at my lowest, i am still filtering my experiences through the eyes of a consumer; the desire to editorialize our own experiences (to romanticize the unseen, to live for our biographies) has become…as unavoidable as breathing.11

I’ll wrap this up by drawing attention to an observation Baudrillard published in 1970: “Our society thinks itself and speaks itself as a consumer society. As much as it consumes anything, it consumes itself as consumer society, as idea.”12 That’s why The 1975 lyrics at the top of this post make sense: we “make an aesthetic” out of everything and “mine” our lives for elements we can offer as consumables.

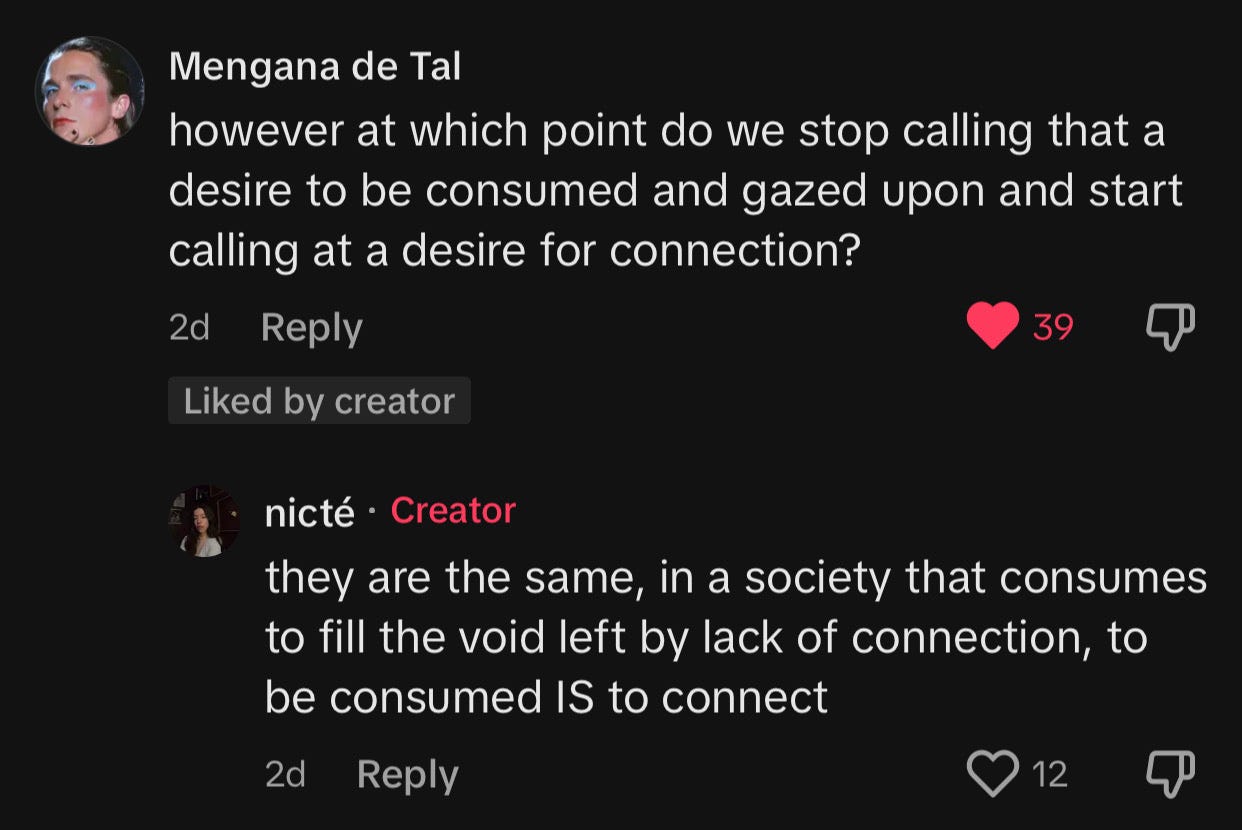

We eat each other. We desire to be eaten, to be consumed, to be wrapped up in something other than our solitary selves. We self-curate to satisfy the appetite of a society trained to devour and to be devoured. As gross as that sounds, it shows that we are more in service to the relational aspect of aesthetic than anything else.

To be consumed is to connect. I’m tempted to draw parallels with Bree meeting Aslan in The Horse and His Boy. “Please,” she says, “you’re so beautiful. You may eat me if you like. I’d sooner be eaten by you than fed by anyone else.” Okay, I’m drawing the parallel because it isn’t entirely wrong to desire to be eaten, to desire to be consumed.

When we self-curate, when we build an aesthetic and offer up our lives on the altar of media, praying for likes, clicks, and words of affirmation to rain down like heavenly fire, we demonstrate this desire to be consumed. But the shadow of that desire is cast by the truer desire to inhabit. To abide and relate. To be fully known. But when we cannot inhabit, we consume and accept consumption as an end in itself.

Our true desire is to live within and to be lived within. That’s why we curate our stories to gain approval or provoke the enjoyment of audiences. That’s why we’re attracted to aesthetic definitions: they provide parameters in which we can abide with others of like flavor. That’s why we build narratives large and small out of our lives.

Narratives offer modes of self-disclosure, ways of connecting our experiences to those of others that aspire to truth… We needn’t be disturbed by this fact if we recognize that the truth of the matter lies not in the original event or even in the original experience of it, but in the joining together of people in communities of self-understanding, that is to say, in friendship.13

inhabit > consume

asides + signal boosts

If this post isn’t as coherent and centered as others, it’s because I was fighting the urge to go off on tangents while writing it—so many tangents—especially when it comes to narrativity as a mode of life. I’m not exaggerating when I say some of what I’ve read the past few weeks has made me actually angry and caused me to question some things that I’ve taken for granted and I might end up writing more about that later.

I’m currenly watching White Noise, the Noah Baumbach x Greta Gerwig film starring Adam Driver and Don Cheadle. I’m really enjoying it and feel like it didn’t get talked about enough because it’s a film film. I especially like the scenes when a small group (the family at the center of the movie, for example, or a cadre of professors) are all in a room and numerous threads of conversation are happening at the same time and it’s confusing, hard-to-follow, but very true-to-life and beautiful to watch. It looks hard to pull off if it’s scripted, but it’s done so well. (This is part of my plan to watch a bunch of Gerwig’s stuff before going to see Barbie in a few weeks. And eventually Narnia in a few years. Eventually Narnia. *insert hopeful gnashing of teeth noises*)

I had the pleasure of meeting Elizabeth J. Birch at a Sputnik art event two weeks ago, and I love her EP Kenopsia and especially the title track. As someone who collects tracks with trippy bass, mysterious vocals, and suspicious, tense electronic vibes, I realy enjoyed it. If you like the same, you’ll like this!

Are all the cool kids going to Threads? Is Twitter the new Facebook? Why is Meta trying to eat the internet? Lots of questions and potential shake-ups in social media this past week. How can I build a consistent aesthetic if the platforms keep changing? (No, that’s not a real question.) Three years ago, I would have cared more. But I compare my social media use now to then and it’s drastically less. Now, I use Twitter (and even Instagram) to keep up with writers and publications and bookmark stuff for later reading: it’s more efficient than visiting all the sites and subscribing to a bunch RSS feeds. But I’m thinking…

Where do you guys think you’ll end up? Will we stick with the social media of our youth till the bitter end?

I enjoy Instagram more of late, I think. Might spend more time there and start posting ‘moodboards’ of the things that inspire these essays and other things I write. There’s a lot that no one sees that goes into every post, and it’s all cool enough that it deserves its own shoutout sometimes.

We’re stuck with “social media” forever. The platforms make it incredibly easy to collate information and sources for information in ways that were simply impossible before, and I don’t think anyone wants to give that up. Even if you’re over the “social” aspect of it, the mediums themselves are still very useful in the exchange of ideas and influences.

Anyway go check out this thread of social media sites as LOTR characters and reminisce over what Twitter is actually good for.

The 1975, “BFIAFL”

Becca Yenser, ‘The Greatest Party That Never Happened’: A study in simulation versus reality, The Sunflower

Becca Yenser, ‘The Greatest Party That Never Happened’: A study in simulation versus reality, The Sunflower

Maria Febiana Christanti, “Instagramable: Simulation, Simulacra and Hyperreality on Instagram,” International Journal of Social Service and Research

Remember these words? “…the stylistically consistent multimodal manifestation of an imagined lifeworld.” (Sarah Spellings, “Do I Have an Aesthetic?,” Vogue, 2021)

Dhananjay Jagannathan, “on telling our stories,”

Galen Strawson, “Against Narrativity,” Ratio (Volume 17, Issue 4), 2004

I can’t get into them all now, but probably will at some point. I wonder, though, if anti-narrativity might save us from an aesthetic hell.

Jean Baudrillard, The Consumer Society: Myths and Structures

Dhananjay Jagannathan, “on telling our stories,” The Line of Beauty