the will to act

It's Men's Mental Health Awareness Month, and what better way to reflect than by considering the evolution of the Dark Knight, that paragon of mental health and emotional stability?

I keep thinking about a particular sequence in Batman Begins. Pre-adolescent Bruce is teary-eyed, panicky, and blaming himself for the murder of his parents. His caretaker, Alfred Pennyworth, is quick to comfort him. “It was nothing you did,” he says. “It was him [the killer] and him alone.”

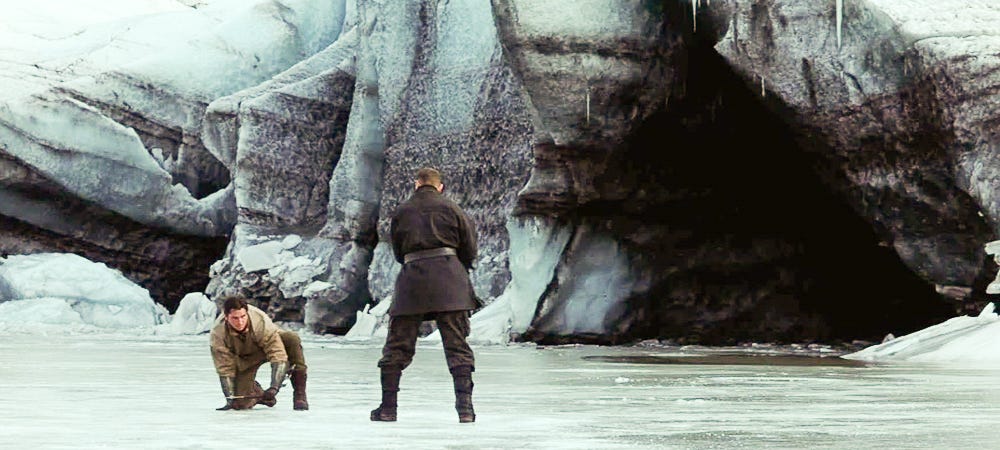

The scene shifts to twenty-something Bruce journeying to find himself and sort out his identity. He’s arrived at the top of a mountain in the Far East. Henri Ducard, a member of the League of Shadows, later revealed to be Ra’s al Ghul himself, is training Bruce to fight and helping him work through his trauma.

Ra’s suggests that Bruce is still bound to boyhood guilt over his parents’ murder.

“My anger outweighs my guilt,” Bruce claims.

Ra’s corrects him: “You have learned to bury your guilt with anger. I will teach you to confront it and face the truth.”

Throughout the fight that follows, Ra’s isn’t so concerned with resolving Bruce’s emotional questioning as he is with shredding Bruce’s inability to act of his own volition and, thereby, decide the type of person he will become. Note the exchange below.

“Your parents’ death was not your fault,” Ra’s says. “It was your father’s…Anger does not change the fact that your father failed to act.”

“[The killer] had a gun,” Bruce protests.

“Would that stop you?”

“I’ve had training.”

“The training is nothing. The will is everything—the will to act!”

At this point, Bruce is in prison. Bound by the past. Bound by guilt and shame. Bound by his lack of direction and a non-existent sense of purpose. He is the epitome of a mewling twenty-first-century youth, casting about in the depths, and adopting the lingua diei as a useful parameter by which to define his ills. He is at the mercy of both society’s whims and his emotions, unaware that opening his sails to the winds of either will set him on course with shipwreck.

“Your anger gives you great power,” Ra’s tells him. “But if you let it, it will destroy you...”

I promise this has something to do with Men’s Mental Health Awareness Month and our ongoing conversation about masculinity and what it means to be a man. It also has something to do with our current cultural conditions, which, I think (gratefully), are inching toward a reckoning with the philosophy of victimhood and the obsessive interiorizing of trauma that have crippled the latest generations of college graduates in the West. Bear with me.

Batman Begins used to be my least favorite of Nolan’s trilogy. But, on recent viewings, it has demonstrated itself a useful periscope through which to gaze at some of society’s ills. At its outset, Bruce is confused and foundationless, capable of pointing out Gotham’s ailments but incapable of figuring out where he fits into the story of his world. He claims to want to do something, anything, to make things right, both in the context of his city and his family. But the place of blame (toward himself, toward others, and toward his circumstances) has become a safe space for him. Self-flagellation (financially, emotionally, and physically) is the only act of which he appears capable.

I’m analogizing Bruce’s condition with the self-flagellatory spirit currently pervading Western society. We’ve hidden behind shame and used it as an excuse for perfectionism and inaction. Shame—about one’s race, one’s privilege, and generations-old historical wrongs—gets thrown like a grenade toward those who dare speak or act. Personal shame over trauma and mental turbulence has become a crutch, an excuse for inaction, for casting around in the mire of existence looking for solid ground.

Shame is at the root of Bruce’s pre-Batman era dilemma. Ra’s pushes him out of this era, not by indulging his sense of shame but by urging him simply to act in the face of it. To make up his mind. To will himself. To exploit his energy. Slowly, Bruce turns from self-flagellation to patience, discipline, agility, and adaptability. These four elements serve him well, not just as a vigilante, but as a man. They are what enable him to develop a sense of purpose and make a difference in his society.

“It’s not who you are underneath, but what you do that defines you.”

This becomes the mantra, the moral lesson, of Batman Begins. Back in Gotham, Bruce stumbles into childhood friend Rachel Dawes during a typical billionaire playboy night out. He’s embarrassed of his behavior and tries to insist, “Inside, I am…I am more.”

Dawes rejoins, “It’s not who you are underneath, but what you do that defines you.” She rightly discerns that one’s actions are the truest reflection of one’s being. Her words push Bruce into a real what (actually) am I doing? reflection.

Later, as Gotham fumigates around them, Batman returns the line to Rachel, testifying to the value of his attempt to save the city. His actions have transformed his self.

Ra’s al Ghul presages this mantra while training Bruce in the early part of the film. Together, they observe a man in a prison cell. “He was a farmer,” Ra’s says. “Then he tried to take his neighbor’s land and became a murderer. Now he is a prisoner.” See the plumbline: The man’s actions defined his being. When he farmed, he was a farmer. When he attempted theft, he became a criminal. His criminal actions turned him into a prisoner. Actions defined the man, not his feelings, his self-doubt, his inconsistencies, or his shame.

I’ll be honest. There’s a part of me that bucks against this sort of thinking. After all, doesn’t God judge by the heart, the seat of the emotions? Yes. However, even in a non-religious context, faith without works, heart without deeds, is dead. We are called to act as evidence of belief. But our actions also fertilize our hearts. It’s a feedback loop. Actions aren’t simply the product of what’s inside; actions also transform and construct what’s inside.

I’m currently making my way through the New Testament letters, and I’ve become obsessed with those passages suggesting the importance of the will to act. There are many, but I’ll highlight a few.

Peter incites readers to “make every effort...to live peaceful lives” and to “work hard to prove that you really are among those God has called and chosen.” He says, “Do these things, and you will never fall away” (2 Peter 3:11, 1:10). The word the NLT translates as “make effort” is the Greek spoudazō which means to exert one’s self—physically, not just spiritually.

In his first epistle, Peter says, “Prepare your minds for action and exercise self-control.” The King James is imprinted in my memory: “gird up the loins of your mind…” Girding, binding up one’s garments in order to prevent hinderance during intense physical activity, is applied here to the will, which incubates in the mind.

James says Abraham’s “actions made his faith complete.”

I could present more, but Hebrews 12 contains my favorites. Verse 14 says, “Work at living in peace with everyone, and work at living a holy life...” Again, the NLT captures the sense of a Greek word. This time, it’s diōkō which means to press on, to pursue a goal (in a hostile manner, with a kind of aggression), to earnestly seek something in order to obtain it.

And look at verse 4—this is so, so good: “After all, you have not yet given your lives in your struggle against sin.” The implication here is of negative action, not a struggle for something, but a struggle against something. Unlike Jesus, none of us (I’m assuming) have resisted personal sin to the point of bloodshed. Many, of course, have paid with sweat, blood, and life in battles against national, corporate, and social evils. But there’s more we can do, more action we must take—in, with, and through our bodies—in order to be delivered from darkness.

None of this negates the power of God or the divine spirit imaged within us. But it does place an onus on what we do with our mattered forms. We can only fully comprehend and experience evil in and with the body. Thus, we must fully combat it in and with the body.

I think I’m getting side-tracked. I’m not trying to emphasize the need to resist evil, although that’s necessary. I am trying to highlight the importance of the will and the importance of action in the development of the self. The core takeaway of Viktor Frankl’s search for meaning is that “man’s inner strength may raise him above his outward fate.” The horrors of the Holocaust, ultimately, could not defeat those who possessed the will to endure. As Rabbi Harold Kushner summarized in his preface to Frankl’s work:

Forces beyond your control can take away everything you possess except one thing: your freedom to choose how you will respond to the situation. You cannot control what happens to you in life, but you can always control what you will feel and do about what happens to you.

Bruce has to learn this lesson to become Batman. While some may have qualms about who he becomes, Bruce’s will to act, his will to control how he feels and what he does about his parents’ murder is the only thing that transforms him from an emotionally-wrecked boy and angsty, misguided young man into a terrifying, elemental, and everlasting symbol.

This has something to do with what it means to be a man or arrive at manhood. When encouraging the Corinthian believers to remain faithful to Jesus, Paul tells them to “act like men.” The Greek word andrizomai means to show one’s self a man. How? By one’s actions. A man is what he does. And what is the engine of action? The will.

“The training is nothing. The will is everything—the will to act!”

There’s little I’d draw exclusively from my experience and declare to be some sort of principle, without first running it through a gauntlet of comparison and questioning. But this is one of those things: the will is a determining factor, perhaps the primary factor, in the course of one’s life. A man who has no grasp on the nature of his will gets tossed by the whims of fate and circumstance. But a man who exercises the muscle of his will, exerting its capabilities over his mind, his emotions, his heart, and his body, determines the effects of time and chance, fate and circumstance, on his person. He does not deny fate or circumstance; he accepts them as handed down from a higher will than his own. Still, he understands that his own will is especially potent. By it, he acts, and by it he gains mastery of self and of some small corner of the universe to which he is committed.

The will is everything!

Take some advice from the Demon’s Head. Bruce Wayne does not become the Dark Knight without the will to act. Boys cannot become men without the will to act. (A toxic version of masculinity is that breed which indulges in inaction, listlessness, and purposelessness.) Our society will not overcome its incompetence, its arrested development, its mental health crises, or its trauma-pervasive worldview without developing the will to act. We must perform with our bodies. We must be willing to bear within ourselves the scars that come from lives of action.

asides + signal boosts

Finally got to watch Godzilla Minus One, the hit Japanese film about a post-WWII found family contending with a dangerous, nation-threatening sea monster. It’s out on Netflix and it’s every bit as good as I heard it would be and deserves all the praise it’s been getting. The storylines are linear, beautiful, and uncomplicated. And the emotional journey packs a real punch. (It also has something to say about being a man, I think.) If you’ve been disappointed by the storytelling in recent box office films—and if you (like me) have never seen a Godzilla movie—give this one a try. It’s totally worth it.

Belly’s new album, 96 Miles From Bethlehem, is a moving and hopeful ode to the people and place of Gaza, currently one of the most tragedy-bound places on earth. Whatever your feelings about the Israeli-Palestinian conflict, give it a listen. Sitting with the stories of another land and its inhabitants—and away from the noise of news reels, protests, and opinion pieces—provides much-needed space for perspective-shaping.

Watch this talk from Jonathan Pageau, Fairy Tales as the Music of the Spheres. Pageau is telling fairy stores with the aim of making their deeper meanings more apparent and highlighting the architecture of such stories to explain why they endure and continue to work on us the way they do.