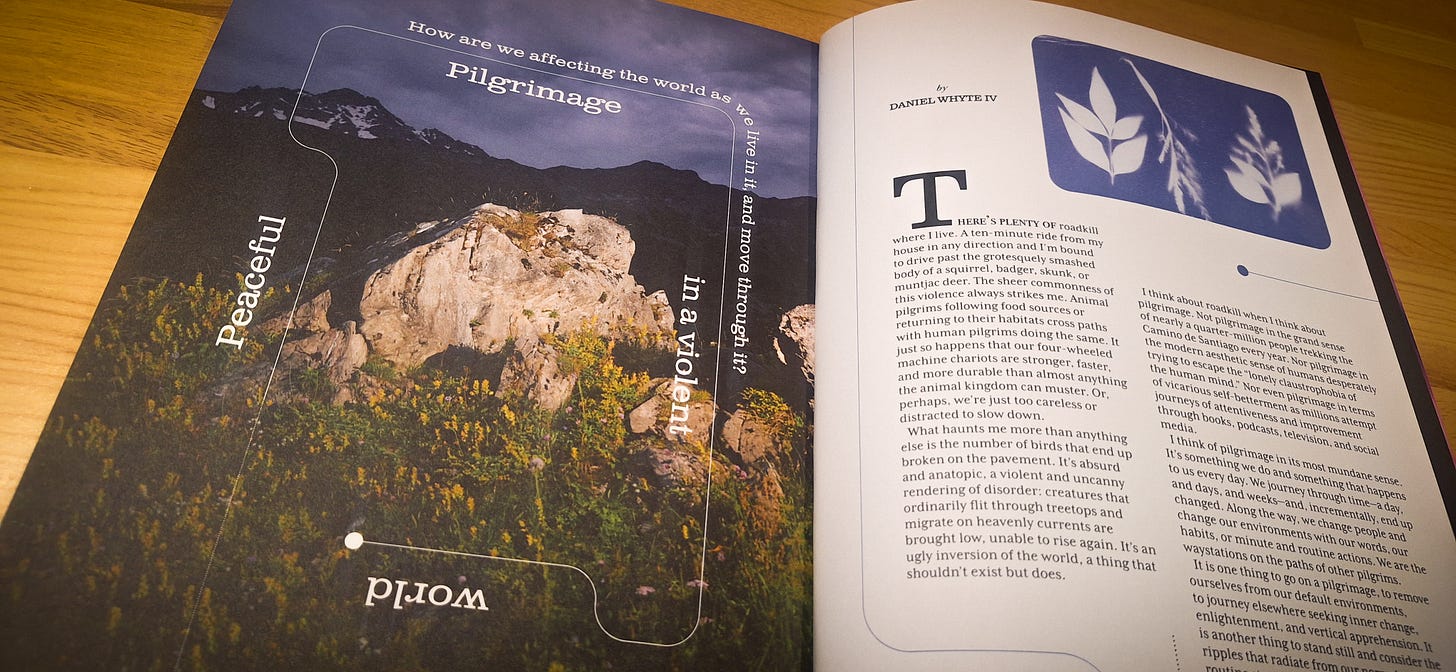

peaceful pilgrimage in a violent world

Exploring roadkill, the Rila lakes, and the resonance of our earthly journeys

A few months ago, I was invited to write an essay exploring the idea of pilgrimage. Thinking about pilgrimage mixed with recurring ponderings on roadkill and a hike in the Rila mountains led to a piece that’s out in Passio’s Autumn 2024 edition—Peaceful Pilgrimage in a Violent World.

Our daily journeys, these recurring pilgrimages, intersect and intercept the daily pilgrimages of others, both human and animal. How do our paths confuse, conflict with, complement, or comfort those on paths that are adjacent or adverse to ours? Abraham, the primeval pilgrim, sets an example of one called via his pilgrimage to bless the lives of people (and, eventually, nations) around him. Pilgrimage is not always about either the big journey or the destination. Often it is about the small journeys and the static life, the ripples we have on our immediate environment wherever we abide.

Here’s the opening.

There’s plenty of roadkill where I live. A ten-minute ride from my house in any direction and I’m bound to drive past the grotesquely smashed body of a squirrel, badger, skunk, or muntjac deer. The sheer commonness of this violence always strikes me. Animal pilgrims following food sources or returning to their habitats cross paths with human pilgrims doing the same. It just so happens that our four-wheeled machine chariots are stronger, faster, and more durable than almost anything the animal kingdom can muster. Or, perhaps, we’re just too careless or distracted to slow down.

What haunts me more than anything else is the number of birds that end up broken on the pavement. It’s absurd and anatopic, a violent and uncanny rendering of disorder: creatures that ordinarily flit through treetops and migrate on heavenly currents are brought low, unable to rise again. It’s an ugly inversion of the world, a thing that shouldn’t exist but does.

I think about roadkill when I think about pilgrimage. Not pilgrimage in the grand sense of nearly a quarter-million people trekking the Camino de Santiago every year. Nor pilgrimage in the modern aesthetic sense of humans desperately trying to escape the “lonely claustrophobia of the human mind.” Nor even pilgrimage in terms of vicarious self-betterment as millions attempt journeys of attentiveness and improvement through books, podcasts, television, and social media.

I think of pilgrimage in its most mundane sense. It’s something we do and something that happens to us every day. We journey through time—a day, and days, and weeks—and, incrementally, end up changed. Along the way, we change people and change our environments with our words, our habits, our minute and routine actions. We are the waystations on the paths of other pilgrims.

It is one thing to go on a pilgrimage, to remove ourselves from our default environments, to journey elsewhere seeking inner change, enlightenment, and vertical apprehension. It is another thing to stand still and consider the ripples that radiate from our normalcy, from the routine steps we take and roads we travel. From the kills we rack up along those roads.

To read the full essay, get your copy of PASSIO: The Journal of Passionist Life here. (Use the coupon code SUBSTACK to get a 20% discount.) Also, check out their substack,

.Thank you to Chris Donald for the opportunity to write for PASSIO, and for heading up such a gorgeous publication. This edition also features (among other things) a conversation on apocalypse with

+ David Benjamin Blower, Francesca Willow’s application of Franciscan principles to the ecosystem of daily life, and a report on the labors of the Catholic Worker Farm to welcome and befriend Britain’s “strangers.”In the essay (the first of mine to appear in a print publication—exciting), I share some reflections from hiking five of the Seven Rila Lakes in Bulgaria this Spring. The hike was fantastic, chilly, gloomy, and a little dangerous. I found common cause with two Australians, a Frenchwoman, a Brit, and a couple from the Netherlands, one of whom was a schoolteacher and the other who was part of an experimental quantum physics program. (When he explained it, it came out sounding like time travel.) I suggested we all grab food together after the hike. But that started an argument over whether the last meal of the day is “dinner” or “supper” and the appropriate time for either meal. We soon overcame that consternation over cultural differences and dined together that evening. It was a good day.

Enjoy some pictures from the hike.