on being worthy

In Thor: Love and Thunder, Dr. Jane Foster becomes the Mighty Thor. But only because Thor loves (loved?) her so mightily that he tells his magic hammer Mjölnir to protect her no matter what.

Before talking about this film with anyone, I knew the criticism I’d hear about the scene where Thor talks Mjölnir into the Jane-must-be-protected-at-all-costs agreement. Oh, no! Jane becomes a superhero because...Thor loved her?!? Because Thor thought her worthy!?! How gross! Her agency is gone. She’s no longer a strong independent woman. Her worth is now tied to some man’s opinion of her. This is bad.

No, it isn’t.

Okay, from a storytelling perspective, it is bad. Jane’s journey from cancer patient to hammer-wielding Thor-woman should have been explored with greater depth. The story short-changed that arc, and Jane becoming the Mighty Thor felt too easy. But I’ll complain about that some other time.

Back to being worthy. (And I promise: this is bigger than Jane.)

I’m going to come at it from a weird angle because I agree: it is a bad look for someone’s worth or worthiness to be tied to someone else’s opinion of them. But it also isn’t. It happens all the time in ways we don’t usually notice.

Once, Jesus’ disciples asked their Rabbi to tell them who would be the greatest in the kingdom of heaven. It’s kind of wild when you think about it because it means at least a couple of them felt themselves worthy enough to be candidates for Greatest Citizen of the Celestial City.

Jesus calls a little child to his teaching circle and says, “Truly I tell you, unless you change and become like little children, you will never enter the kingdom of heaven” (Matthew 18:3).

That’s probably not what the disciples wanted to hear because little children had no significance in first-century Jewish society. No one was going around telling kids, “You can be whatever you want when you grow up.” Or encouraging them to have high self-esteem. Parents didn’t storm into Sabbath School, taking up arms against the teachers who had the gall to tell little Jeremiah he couldn’t “express himself” by drawing funny faces on the Torah scrolls.

No, children were little runts and they knew it.

The most powerless members of ancient society were little children; in most of ancient society, age increased one’s social status and authority. In Jewish culture, children were loved, not despised; but the point is that they had no status apart from that love, and no power or privileges apart from what they received as total dependents on their parents. (Keener, C., The IVP Bible Background Commentary)

If you’ve been in church for some time or Christian-adjacent, you’ve probably heard the whole be like a little child spiel. But it’s usually taken to mean being humble or quick to believe. But that’s not what it means entirely.

When Jesus tells us to change and be like little children, he is telling us to accept our place as nobodies. As powerless and privilegeless in a society that runs on power and privilege. As worthless. As unworthy.

But that’s the twist. Little children are worthy precisely because they can’t be worthy on their own. Because someone (a big adult human) looks at them and says, “That’s my child. I love that little runt.” And entirely because of that claim of mine!, the child is suddenly worthy. The child has power and status because someone else chose her and determined her standing for her.

It is precisely what Paul is ranting about to the believers at Ephesus. God, “because of his great love for us...raised us up with Christ and seated us with him in the heavenly realms.” They (and we, who are “by nature deserving of wrath”) are made worthy to sit in high places precisely because we aren’t worthy to begin with and God is over here choosing a bunch of nobodies and glitter-bombing them with worth.

We’ve all done favors for people out of a sense of obligation. Oh, I have to. Or, if roles were reversed, I’d want them to do it for me.

But we also do things just because we like people and because we want to. Little gifts given or favors shown. A pause for conversation when we wouldn’t pause for anyone else. There are people who I will stop and talk to, drop anything and run to help. In those moments, I am assigning worth. I am saying, “You are worth the time and effort. You are worth the extravagant expense.”

If that is a bad thing, it is also beautiful.

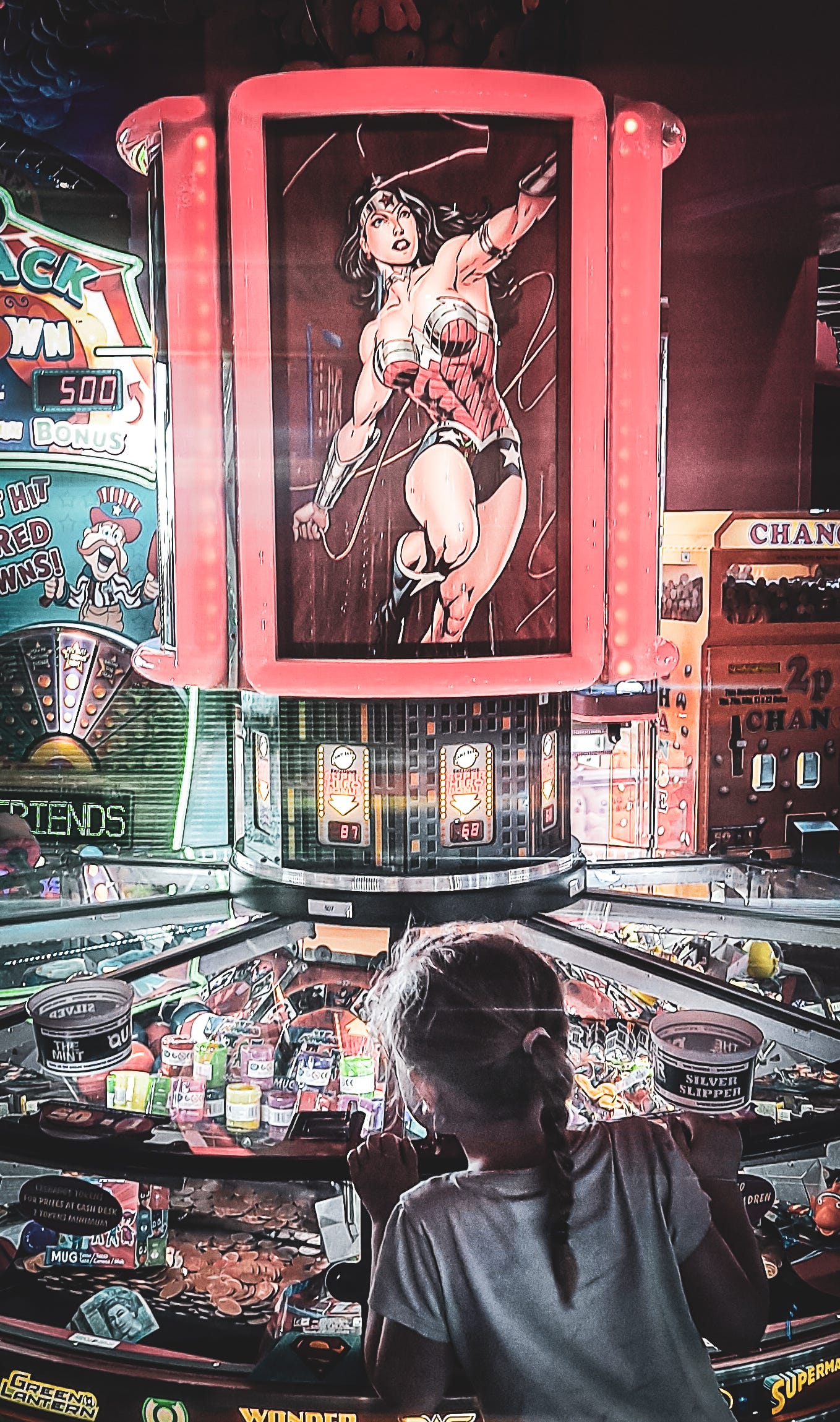

And that is what Jane’s journey to being the Mighty Thor helped clarify for me. It is not an intrinsically bad thing that she is deemed worthy to wield Mjölnir primarily because Thor loves her.

Yes, we have intrinsic worth as beings crafted in the divine image. But that doesn’t get us very far on a practical level.

Instead, we live in an economy of worth. We seek it and we give it. And on the plane that reaches closest to divinity, we find our worth when we realize we aren’t worthy and revel in the worth granted us by others.