let's try and have a nice disposition (Wildcat!!!)

Uncoordinated thoughts on the Flannery O'Connor film, other movies recently seen, and some songs of strength + escape

(programming note) I drafted this post in late August. The weeks between then and now have been a wicked rollercoaster which I may or may not share more about down the road. The months ahead will be filled with haste and change; Very Public Secret Society will roll in uneven waves. I’ll write and share—mostly things I’ve already partially drafted—as time and energy permit (and to keep my sanity). The subject of this post, a writer who wrestled with tragedy, self, doubt, and faith, is (in my feeble judgment) fitting as a return to form. I’ll let you know when a steadier publishing schedule is on the horizon.

It’s nice when you’ve been looking forward to something for so long and it finally arrives and does not disappoint. That was my experience watching Wildcat, Ethan Hawke’s drama biographic about part of Flannery O’Connor’s life. Maya Hawke delivers a ceaselessly captivating performance for a film where she portrays not only the main subject, but a character in each of the six stories the Hawkes chose to depict.

Wildcat throws the viewer in on the deep-end, opening with a fictional black-and-white promo for a dramatization of “The Comforts of Home,” one of (from my observation) O’Connor’s less-referenced stories. The film walks through the early days of Flannery’s success up until she settles with the hammer blow of lupus. For her, the disease which killed her father means a life stuck in the small Southern context of Milledgeville, GA—a context she once believed she needed to escape lest it hinder her pursuit of literary success.

Thank God she was bound.

I’ll admit to being a Flannery fanboy. And it’s fair to assume that condition might make me a lenient critic. But I beg to differ: I think it makes me harsher. I wanted Wildcat to be really good and I think it is. Maya as Flannery is believable, and the partial adaptations of O’Connor’s short stories—“The Violent Bear It Away,” “The Life You Save May Be Your Own,” “Parker’s Back,” and others—are, in vernacular terms, comic accurate. The adaptations are so accurate, in fact, that they err against present sensibilities to the point of depicting dream-Jesus offering Ruby Turpin the option to “either be a nigger or white trash.”

Wildcat is beautiful to watch and listen to. I watched the film for a second time on my iPad with noise-cancelling headphones while putting together a set of drawers. Even when not focused on the screen, I enjoyed hearing it—not primarily the soundtrack or the sonic ambiance, but the dialogue. Much of the lines are drawn from Flannery O’Connor’s letters; it’s remarkable. This adaptation of a real life feels like the life it is trying to adapt.

My third viewing was with my siblings back home in Texas. They certified it as a good film and I’m pleased they liked it because, sometimes, they are harsher critics than myself. (Perhaps, they have yet to mellow with age as I have.)

The film does an excellent job of sifting between O’Connor’s struggle to publish her novel, her wrestling with editors, industry demands, and audience expectations, and the seeds of her short stories—ordinary people grappling with their unique idiosyncrasies and environments while trying to live up to some sort of ideal. That ideal is encapsulated by the stereotypically Southern quality of having a “nice disposition.”

While riding back from the train station to Milledgeville, Flannery’s mother admonishes the young writer to “try and have a nice disposition” and her aunt suggests she “write about nice people” next time. Both are concerned about the peculiarity of Flannery’s stories—and peculiarity is putting it mildly. They prefer something like Gone With the Wind, a story where everyone is in their proper place according to lingering prejudices and norms.

Wildcat repeatedly returns to the theme of the “nice disposition” and Flannery’s family’s insistence on her being “nice.” Flannery never argues against the idea, preferring to let her stories speak for themselves. She doesn’t write about nice people because nice people don’t exist. Ugliness sits below the surface of the pre-Civil Rights era South. Flannery’s writing rips up the surface and exposes the ugliness in the people who would consider themselves nice.

And that doesn’t have to be seen as judgmental either. The brilliance of Maya Hawke and Laura Linney playing Flannery and Flannery’s mother (respectively) along with taking on starring roles in the film’s mini-adaptations of Flannery’s short stories is that it emphasizes that she was writing to her people, about her people, and for her people. Yes, her stories are pointed and retributionary, but she isn’t preaching at/to the crowd. She’s in the crowd; that’s why she understands them so well. That’s why her stories bite.

The encouragement to be nice reflects on our present collective impulse to be publicly good, or correct, or not say the wrong thing, the thing that would put one outside of society’s good graces. Of course, it’s good to be nice, to try and have a nice disposition, to cover, even, a multitude of sins. But improvement of our collective moral condition does not come without ripping the band-aids off our wounds—or being thrown to the ground as the tractors we’re riding crash into trees and burst into flame, as the situation were.

This reminds me of another metaphor used in the film. (I’m taking it as a metaphor whether it was intended as such or not.) O’Connor’s love of fowl, especially chickens and peafowl, is well-known. Near the end of the film, Flannery’s mother criticizes the peacock her daughter has finally gotten. The creature had been eating everything in the garden, including her roses, and destroying vegetation by sitting on it. “What good is he? He doesn’t even put up his tail feathers,” she complains.

“Nothing ails him,” Flannery says. “He’ll put it up. You just have to wait.”

I like to think Flannery O’Connor is like her peacock. Trampling sensibilities, devouring the subjects of her stories, scorching the earth with her words. What good is she? She never really put up her tail feathers. Except she did. She really did. Folks just had to wait.

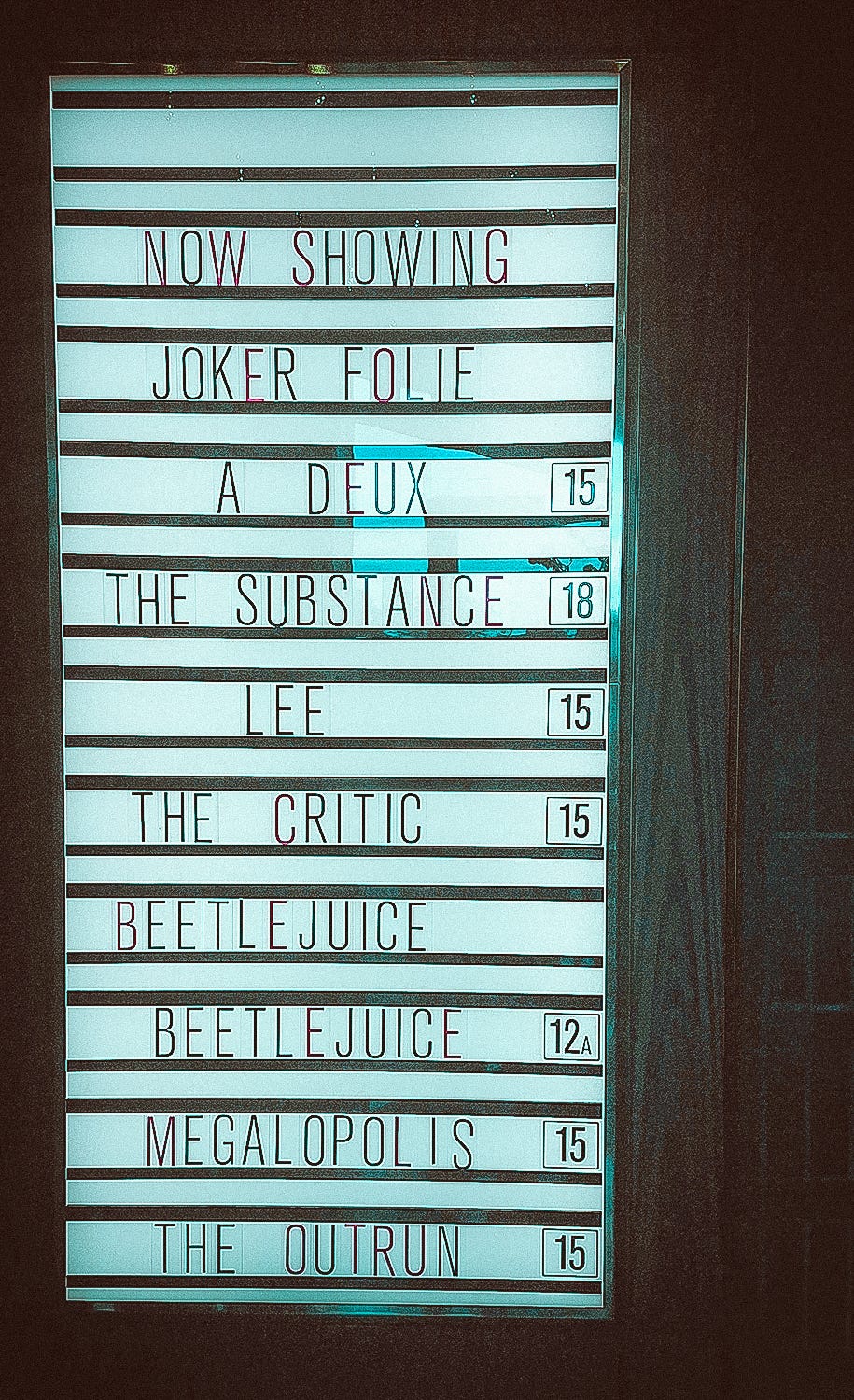

other movies recently seen

The Ministry of Ungentlemanly Warfare. This movie knew what it wanted to be but just…never committed fully. Henry Cavill couldn’t save it. Honestly, a waste of effort.

Your Name and Suzume. Both are visually gorgeous, lush with color and profusive creativity. The first being an achingly beautiful disaster story with a heavy suggestive romance and the second being a brilliant fantasy adventure with plenty of heart and humor. Will likely watch these again.

Civil War. All the chatter about this one had me worried it’d be underwhelming. But it’s brutal and hard and leaves an impression. It’s not so much about the civil war as it is about the journalists’ journey and their ethical dilemmas along the way. I’ve no love for the dense critics who tried so hard to get this film to ape America’s current political strains.

Lee. Another hard film that deals with unholy realities. It’s as much about fashion-model-turned-war-photographer Lee Miller as it is about the ugliness of war and a good depiction of the dawning realization of the depth of Nazi cruelty.

songs of strength + escape

As some of you know, the past few weeks have been especially hard for my family. Music is often a comfort train for me, a strengthener, an escape. Sharing some of the tracks I’ve had on repeat below.

Also: I’ve run this playlist, inspired by the work of Brazilian rapper Silas Magalhães, in the middle of the storm.