what's to be done about a society with low appetite?

Andor, Emily in Paris, and how to solve our cultural crisis of apocalyptic bad taste.

I had doubts about Andor from the start. After the lax horror that was Obi-Wan Kenobi and the muddled, direction-lacking Boba Fett, I wasn’t sure I wanted to give another Star Wars series several of the already scarce hours I allow myself for screen-watching. It didn’t help that I fell asleep on the first episode. Twice.

But the third time was the charm, and watching Andor was like taking a breath of heavenly air.

The scriptwriting? Immaculate. Dialogue and delivery? Gorgeous. There was none of the smirking witticism that’s become par for the course in big fantasy and superhero franchises, none of that smug cleverness and above-it-all humor. Each performance held tension between anticipation and delivery. Every scene both fed me and kept me hungry. Andor reminded me what a good story made for the screen is supposed to feel like.

Documentary filmmaker Houston Coley rightly lauds Andor as “elegant, empathetic, subversive, thoughtful, and perhaps the first piece of Star Wars media to elicit tears of both righteous anger and emotional catharsis.”

bad taste all over the place

Watching Andor makes it easy to see what’s missing in the entertainment landscape: patient storytelling, dexterous writing, skillful acting, canny plotting, and the embellishment of themes that subsume the viewer—all in the same story. Much of everything else theaters and streaming services have to offer is lacking. Some of our present-day entertainment options are so shockingly bad it’s surprising people get away with making them.

I’m no high-brow viewer. I’ll tolerate Warrior Nun and Shadowhunters and She-Hulk. They aren’t the worst things ever, and sometimes I want to shut my brain off and be entertained. But compared to Andor, they’re middling at best.

A few weeks ago, I hung out with a friend who was bingeing the Netflix reality show Single’s Inferno. After watching over her shoulder for a few seconds, I wanted to gag. She admitted it was cringey and delusory but kept watching anyway.

Take this tweet from Atlantic writer Elizabeth Bruenig1 and replace “emily in paris” with the title of a random show you haven’t watched, and it won’t be far from the truth.

Why is there such a glut of malicious, incoherent, and astoundingly dumb media? Yes, it’s easier than ever to make things now. Anyone with an idea, a video camera, and a few bucks can start a streaming series. And Netflix’s tactic of developing for niche groups ensures that someone will always be willing to watch almost anything.

But it’s not just makers who are at fault for poor content. It’s the audience too. Our society has bad taste and low appetite. We eat what we’re fed, but the chefs are cooking up exactly what we’ve ordered. TIME’s TV critic, Judy Berman writes:

We have entered an era of exuberant, even apocalyptic, bad taste… what we’re witnessing goes far beyond cool teens and the extremely online to encompass anyone with free time, disposable income, and internet access... What we’re dealing with is a full-blown cultural moment.

Of course, some would argue that taste, like beauty, is in the eye of the beholder. If that’s the road we’re going down, I’d better pluck my eyes out and cast them from me now because I’ve seen too much awful media. To be fair, what’s significant and compelling to one generation might seem infantile and ridiculous to another. Debates over what’s culturally important are going to happen. But the thing about good entertainment media is that it endures. This is easier to see with music and books because we still have access to those from past centuries and millennia and we constantly rejudge their viability.

Moving pictures were barely a hundred years old when Peter Jackson made The Lord of the Rings, but people will still be talking about that trilogy five generations from now.

The Fast & the Furious? Eh, not so much.

There will always be low art. It has its place. But I’m appalled at how much of it there is right now. And how easily and enthusiastically we embrace it. “What’s remarkable about this particular pendulum swing,” Berman writes, “is that after centuries of wrestling with hierarchies of taste, the cultural stigma that has always come with indulging in bad taste has disappeared.”

hot and cold, high and low

In his 1964 work, Understanding Media: The Extensions of Man, Canadian philosopher Marshall McLuhan articulates the idea of hot and cold media. A “hot medium” gives much detail to the audience and requires little interaction for communication to occur. A “cold medium” gives little detail and requires more interaction for communication to take place. For example, to McLuhan, the radio was a hot medium while the telephone was a cold one. The radio audience must merely lend an ear to receive the entire message, while the telephone answerer must speak, think, and listen. But this is the important part:

…hot media do not leave so much to be filled in or completed by the audience. Hot media are, therefore, low in participation, and cool media are high in participation or completion by the audience. Naturally, therefore, a hot medium…has very different effects on the user from a cool medium...

Fast forward a few decades, and we have a similar distinction being drawn—not between different mediums this time, but between different types of people. University of North Carolina researchers studied differences between people who watched Harry Potter and Lord of the Rings movies without reading the books and those who watched the movies only after reading the books. Results showed a distinction between individuals who have a “high need for cognition” and those who have a “low need for cognition.” Per the study:

Need for cognition is the tendency to enjoy and engage in effortful cognitive activity.

I’ll now propose two parallels.

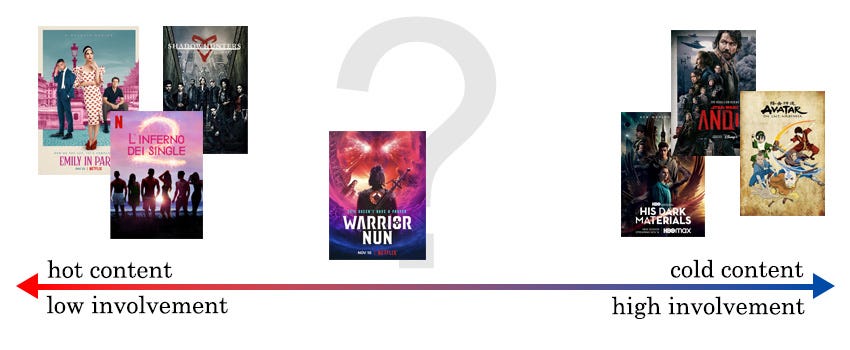

McLuhan’s hot-cold scale can be applied to content in the same way that he applied it to media. There is hot content and cold content. Hot content is easy, accessible, and demands little of the imaginative and cognitive abilities of the audience. (Think Emily in Paris.) Cold content may appear inaccessible, but it simply invites the use of more of the audience’s imaginative and cognitive abilities. (Think His Dark Materials.)

Similarly, just as the UNC researchers apply need for cognition to people, it can be applied to media content itself. However, we must expand the implications of cognition when interacting with media content: movies and shows don’t solely involve audiences intellectually, but emotionally, imaginatively, psychologically, and even spiritually.

The point is: some art-media2 demand higher involvement. These are the offerings that stick with us, that make us think, that we return to again and again. As Coley writes of Andor: “it does require some focused grown-up attention…” Most media offerings today do not require such attention or intensity of the audience; they are low in need for cognition and low in the demand for involvement. What you see on the first go is all they have to offer. They are easy to digest.

And this might explain why so many streaming series, after being lauded by audiences, end up on the chopping block after a single season. They offer no critical meat to keep an interested audience coming back. On a scale of chicken noodle soup to shepherd’s pie, they are like chicken noodle soup without the chicken or the noodles. Easy to slurp down but useless for rumination.

I’ll sum this up with a graph:

Most of the art-media presented to us today exist on the hot content x low involvement end of the spectrum. And this is bad.

low appetite transformed

“Trash has given us an appetite for art.”

Berman cites those words from film critic Pauline Kael’s 1969 essay, “Trash, Art, and the Movies.” And I believe they’re true.

Last year, a friend related her experience watching the 2010 Last Airbender movie. She liked it. A lot. And then she watched Avatar: The Last Airbender, the highly acclaimed 2005-2008 Nickelodeon television series from which the movie was adapted. Now she won’t touch the movie again, because the television series was so much better—full of direction, themes, emotions, and storytelling prowess that cause many to regard it as the greatest animated television series of all time.

I pointed out that if she hadn’t watched the movie, she probably would have never watched the television series on which it is based. The Last Airbender satisfied her appetite at the time, but Avatar (the television series) satisfied an appetite of a higher order.

Berman again: “In other words, the scrappy subversiveness of B movies can ignite a passion for more sophisticated cinematic subversion.”

Some art-media sates the audience’s low appetite. Our mistake is when we misinterpret this sating for the indulgement of a real meal and click thru the Netflix menu watching appetizer after appetizer. There isn’t anything wrong with art-media that sates a low appetite. Such art is necessary for those who have low appetites—and we have all had them at some point. (We often revert to them even now.) What is needed is the transformation of our low appetites into high ones, where we expect art to engage us on multiple levels and in numerous ways—intellectually, spiritually, emotionally, psychologically. We cannot be satisfied nibbling on snacks all day when what we need is a four-course meal.

Culture produces art, but sometimes art produces culture. From the ‘70s to the ‘90s, there are numerous examples of entertainment programs—telenovelas in South America, rock songs in Mexico, and radio and television dramas in India, Jamaica, and developing nations in Africa—shaping cultures for the better.

Art has the power to mold the appetite of the audience. And appetites are not molded by appealing to what Berman calls “the sense of doom that makes a person desperate just to feel something”—a sense alleviated by “a sensory onslaught [of] color, sound, hedonism, melodrama, [and] sleaze.” Appetites are molded by awakening the audience to its deeper desires, by demanding that the audience feel something more.

losing our taste for hell

Society’s low appetite is a matter of desire. The problem is metastasized by our aggressively online lifestyles, which have led not only to shortened attention spans but shortened attentive ability. And an audience lacking in attentive ability will find vapid, vain, easily accessible, and easily digested content more attractive than art-media that makes serious demands and appeals to serious desires.

We are collectively disengaged from media with substance and depth. An era of trending topics, hashtag wars, and a news cycle often dictated by social media drama is rewiring our brains to persistently look for the next thing to trigger a quick feeling: outrage, shock, excitement, fear. If the Council of Nicaea happened today, the only thing the public would know for sure is that Nicholas slapped Arius in the face3 (#SlapHeardRoundtheWorld). And then we’d move on from that to the next big thing.

This tragic cycle reshapes our desires. It bequeaths us a low appetite. We want snacks because we’re becoming incapable of handling a real meal. We want a tweet instead of an essay, a TikTok video instead of a documentary. Or, as the Apostle Paul would say, we desire milk instead of meat.

Later in his chapter on hot and cold media, McLuhan writes: “We live mythically but continue to think fragmentarily and on single planes.” His context was slightly different: social media didn’t exist back then, but McLuhan did predict the “global village” brought together by technology and access to information in which we now live. However, the fragmentary thinking that the Internet era fosters is the enemy of mythic intuition, an intuition that is buried by low appetite.

Myth, according to McLuhan, is the instant vision of complexity.4 A low appetite robs us of the ability to engage with complex, layered stories that act as windows to the “mythic dimension.” But we can regain this ability. We can cultivate our desires and the desires of those around us.

It’s far easier to go on a “five-hour brain vacation” with Emily in Paris than to wrestle vicariously with questions of existence and purpose via Andor or Orphan Black. But we foster a high appetite via the discipline of engaging with art that satisfies a high appetite. Once we have eaten the four-course meal we will not want to go back to warm milk.

Or, as the Yeah Yeah Yeahs sing: in heaven, we lose our taste for hell.

I am not saying that we must always try to use art-media to further our emotional, spiritual, or intellectual growth. (I like watching stuff that’s fun and dumb as much as the next guy.) But I am saying that the media we consume—all of it, even the stuff we watch for fun—folds the origami of one’s soul ever so slightly and skews how we see ourselves and the world. This is inevitable.

I am not so much concerned with moralism or worldview in the art-media we consume and participate in. That discussion has its place. But in a world where so much art-media shutters vision and closes minds, I am concerned that what I watch helps me think and see and sort out the complexities of being—and strengthens the muscles used to do so. Otherwise, those muscles atrophy and I’m left incapable of high appetite. (Basically, I’m asking: is this show making me smarter or dumber?)

The thing is: we’re all busy living vicariously—if not physically—as if we’re immortal.5 But much of the media we are satisfied to consume does not help us live as immortal creatures. We submit to epically bad desires and low appetites and think we are fulfilled. But our desires, as C.S. Lewis put it, are too weak. “We are far too easily pleased.”6

asides and signal boosts

Towards the end of the latest episode of The Reason Roundtable podcast, Katherine Mangu-Ward (Reason editor-in-chief) revealed she and her family were having a “winter of God.” Despite being “abysmally ignorant” about religion, she’s been taking her kids to religious services and spending time afterward Wikipediaing herself into religious literacy. If you’re not religious or identify only as “spiritual,” you should do this too! Jump in on the deep end: go to a church or synagogue or temple and be deliciously confused and perhaps horrified. Awaken yourself to matters beyond this physical realm! Here is not all there is!

Also check out M.I.A.’s recent profile in Relevant, in which she talks about her journey from “being 100 percent comfortable in Hinduism” to realizing “it was a Christian God that turned up” to save her. Which is where I hope you end up because Jesus is terrifyingly awesome.

Mostly, I hope God gives you the grace to get your shit together (as Liz Bruenig once put it in yet another epic tweet now lost to the sands of time).

Ekstasis Magazine recently started a substack called Ecstatic. I subscribed to it because—well, if you’ve read Ekstasis you know why—and you should too. Anyway, I was ecstatic (ha ha) when, a few days after I started working on this post while thinking heavily about the “consistently vacuous” Emily in Paris, I got an Ecstatic substack email with a reflection by Yi Ning Chiu on nothing other than Emily in Paris, which I subtly linked to above. (Great minds think in tandem.) But you should read the whole thing too.

If you happen to live in the UK or Ireland, go see the National Theatre’s adaptation of The Ocean at the End of the Lane. It’s currently on tour to 25+ cities. I saw it in London last year, and I can confirm it is art that satisfies high appetite and strong desires. The “thrilling adventure of fantasy, myth, and friendship” adapted from the novel by Neil Gaiman is brilliant and emotive! If I get a chance to see it again, I will.

Unfortunately, Liz Bruenig no longer tweets. But some of her epic missives live rent-free in my head. Also, I have screenshots.

I’ll use the term “art-media” repeatedly to avoid having to say, “movies, TV shows, and streaming series” over and over again.

Even though he probably didn’t.

McLuhan, in the second chapter of Understanding Media, is talking about myth as it pertains to the advent of the “electric age,” but his points are relevant to us living in the information and internet age as well. “…myth is the instant vision of a complex process that ordinarily extends over a long period. Myth is contraction or implosion of any process, and the instant speed of electricity confers the mythic dimension on ordinary industrial and social action today. We live mythically but continue to think fragmentarily and on single planes... Our inner experience, increasingly at variance with these mechanical patterns, is electric, inclusive, and mythic in mode.” There’s more where that comes from.

Crediting Berman’s TIME piece for the wording arrangement in this sentence. She was refering to life during the pandemic, so it’s not a proper quote, but still a valuable insight.

From The Weight of Glory, an essay-speech by C.S. Lewis.

Opinions on Motherland: Fort Salem? I’ve been convicted about watching it due to the content but I think it does satisfy high appetites as it asks questions about our world through use of alternate reality.

Billy Madison’s Academic Decathlon finale speech would fall on the hot content/low involvement end of the spectrum, as everyone in the room was then dumber for having listened to it.